Chris Jones, Author of “The Swine Republic,” on What (and Who) Is Behind Iowa’s Water Problems

Ever since he began his blog in 2016, Chris Jones has provided a counterpoint to the farm industry’s mythologizing about the soundness of some of its practices. A research engineer in Iowa, he until recently oversaw a network of sensors that measured nitrate levels in the state’s rivers and streams — which, as tributaries of the Mississippi, have had an outsize hand in creating the dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico. Jones understood the precarious position he was putting himself into by writing about the intractability of Iowa’s nitrogen- and phosphorus-polluted waters, calling agriculture and the politicians who prop it up to account. His blog was hosted on the website of the University of Iowa, his employer, which is funded both by the state and by agribusiness.

In April of 2023, Jones saw his blog shut down under pressure from legislators, he said, and the budget for his sensor network cut the following month by the Iowa state legislature. In between, he resigned from his university post.

But on May 19, Jones released “The Swine Republic: Struggles with the Truth about Agriculture and Water Quality.” In a collection of essays originally published on his blog, supplemented with some original material, Jones introduces new readers to his historical perspective on “what happened to Iowa” — tile drainage to convert wetlands to farmland, non-stop corn production at the expense of all other crops, the ascendancy of feedlots and the creation of a system that dumps and leaks chemical inputs and animal waste on a massive scale. FoodPrint talked to him about the blog, the book and why Iowa’s water woes are not likely to be solved anytime soon. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How would you describe the overarching theme of your book?

[It’s] that the political and agricultural establishment here in Iowa refuses to be honest with the public about the environmental issues connected to agriculture. I’m a scientist, and if we’re going to solve this problem — which is a gigantic problem — we need to be honest about what the causes are and what the solutions are, and what they’re going to cost.

How much of a readership have you attracted to this somewhat niche subject over the years?

In total, the stuff [on my blog] has been read about 200,000 times. Is that big? I don’t know, but I think I did reach some people. The fact that the essays were on the university domain gave them sort of a fearless character that they otherwise might not have had.

You write about Iowa having the most polluted waterways, but is this a bigger problem than just Iowa?

There’s other states with similar problems in the Corn Belt. But there’s two things that separate us. One is the dominance the industry has in our legislature; I think “stranglehold” is a fair [word]. And the other is, Wisconsin, Minnesota and Illinois have large urban centers that provide a political counterbalance to the industry. Kansas and Nebraska have similar politics [to Iowa] that are joined at the hip with agriculture. In Kansas, especially, the issue is water availability: The Ogallala Aquifer is being sucked dry to produce corn for ethanol and feed for livestock, and it will take 6,000 years for that water to naturally replenish. The big problem emerging now in Nebraska is nitrate pollution in drinking water in rural wells. This was something that Iowa went through 30 years ago.

So yes, there’s problems elsewhere, but I do think there are some things that are unique to Iowa — like livestock. Illinois, for example, has a very similar number of crop acres as we do, and the mix of corn and soybean is very similar. But they don’t have the magnitude [of] the problems that we do because they don’t have the livestock. We have 25 million hogs, [115] million chickens, 4 million cattle, and 12 million turkeys. We have all…the problems associated with that, plus all the problems linked to crop production.

The other big thing is [that] so much of our state is farmed. Everything that can be farmed here is farmed. We have a problem of scale. You go to Minnesota, and you see that, while they have a lot of hogs and they have a lot of crops, there’s a lot of [land] they can’t farm. When you leave portions of your state in a relatively undisturbed condition, that buffers the effect of this intense production.

You write about industry-funded science that keeps studying water issues. Is enough known about how to fix Iowa’s water problems to just do it?

When I worked at the Des Moines Water Works in the early 2000s, already Iowa Farm Bureau was saying that stream nitrate was from rotting leaves, combined sewer overflows, wildlife and golf. We knew then what the [main] problem was, but the industry’s response to these environmental things [was] deny, distract, delay. Now they’re in the delay stage, [even though] there is some recognition that they are causing the problems. A point that I make in the blogs that has not made me many friends is that academia is a big part of the problem — because we are willing to study things over and over and over again if somebody is paying us to do it. We mapped the human genome after 30 years, but after 100 years we still can’t figure out how much nitrogen to apply to corn. The reason is, the industry wants us to keep studying that stuff and parse out the minutiae…because that distracts from the real issue. And that is: that we have a problem with scale, and we have a completely unregulated system.

Are non-farmers beginning to understand more of this picture?

The number of farmers in Iowa has dropped quite dramatically [in the last few decades], like it has in the rest of the country. But we still have 85,000 [at least part-time] farmers, and almost everyone who’s grown up here knows somebody that farms; they’re all 65-year-old white guys. I call them Uncle Harold. Yeah, we know that some of what Uncle Harold does is bad for the environment. But Uncle Harold, he’s a good guy and he sent me $20 on my birthday, and I don’t want to step on him while he’s alive. But the truth of the matter is, these guys are all millionaires making way more money than the average Iowan. I think there’s some people that are [starting to understand this], but the industry knows the ropes on this very well. That’s what’s behind this rhetoric of the family farm. “If it’s a family farm, how could it be bad?”

You point out that Iowans vote for clean-water legislation that gets overridden. Are there ways to break through that block?

When I go out and give programs and presentations, inevitably somebody asks, “What can I do to make things better?” And also inevitably, somebody shouts out, “Vote!” I don’t buy that. The idea that you can vote for the Democrat and expect change, I think, is a fantasy. There’s got to be some grassroots demands. The Grange is still around. It was a grassroots farmer organization over 100 years ago that was formed to fight the monopoly the railroads had on grain. There was a National Grange with thousands of local chapters. They went to local meetings — city council, county supervisor, whatever — and they agitated for change that would beat these monopolies down. They were very effective, firstly, because all the local chapters had local control and the national chapter did not intervene. What I tell people is we need a Grange for water quality. In Iowa, we have 3,000 of what are called “drainage districts” for the organized tile drainage systems — we know tile [drainage] is a big problem. When county supervisors are meeting about the drainage district, there should be somebody agitating for water quality, asking, “How are these decisions going to affect the creek the district drains into?”

How does the agricultural history of Iowa fit into its water issues?

It’s what we call the “drunken walk” — it’s a statistical problem. When a guy leaves a bar and he’s drunk and he’s trying to walk home, he doesn’t walk in a straight line; he walks zigzag, and each step is made independently of the previous step. He gets from point A to point B, but he might not make it home. That’s what we’ve had here, the drunken walk; agricultural decisions were made to do one thing or another maybe a century ago, and those are baked in [then other decisions were layered on top].

One of the big decisions was to drain everything: We put in all this draining tile prior to 1910 to lower the water table. That’s the source of a lot of our problems, and the idea that we should straighten streams to square up fields for farming — in the ‘30s that maybe seemed reasonable to people, but now, it’s an ecological catastrophe. The other big thing in more recent times is the emergence of soybeans. We really didn’t grow many soybeans here prior to the 1960s. Then, it became an all-cash crop all the time. Soybeans did not displace corn; soybeans displaced alfalfa and oats and barley and sorghum. Some of these other crops that farmers grew were legumes like alfalfa and clover that provide nitrogen for corn; soybeans can’t do [that]. So when we brought in soybeans, not only did we displace these crops that were less environmentally degrading — we also had to bring in commercial fertilizer [for the corn]. [But] the timing of fertilizer applications does not synchronize with when the corn needs it, and as a result, we have all this nitrogen [leaching into water]. When we’re relying on legumes to provide nitrogen, then everything is in sync.

Do you think there needs to be federal oversight of agriculture?

The best thing that ever happened for Iowa in agriculture was conservation compliance in the 1985 Farm Bill [which] requires farmers that are farming on Highly Erodible Land (HEL) to adopt a soil conservation management plan in order to be eligible for federal farm programs. If you could point to any single thing that has produced the most beneficial environmental outcomes, it’s that law. If we know that works, why don’t we try it for other things, like nutrient pollution? But even Democrats have put all their faith in the markets, and you can see that [Secretary of Agriculture Tom] Vilsack wants “climate smart commodities,” with the expectation that people will be willing to pay a premium for these. I’m 62 years old. I’ve lived [in Iowa] most of my life. The water has been bad my entire life. We have a right to expect something better.

You hedge in your book on blaming water pollution on farmers. Why is that?

There is a system in place where we have a lot of economic infrastructure that follows this corn–soybean funnel. People in academia are partly to blame. People in agribusiness are to blame. The insurance industry, the banking industry, the politics are all part of this. You don’t get this condition just through the actions of 85,000 guys. It’s a team effort. Look at ethanol: We’ve created this guaranteed market for corn, and because of that, the land has become increasingly valuable over the last 20 years. Now we have farmland that sells for $25,000 an acre. What are you going to plant on that? You’re not going to plant potatoes. Can you blame the farmer for [planting corn]? Will the environmental condition get so bad for farmers that they themselves demand change? There’s some of them around, not many. But change is gonna have to come from the farmers. They’re the ones that hold the power.

Where do you see Iowa going from here?

One fifth of our state is used to grow corn for ethanol. [But the] emergence of electric vehicles is reducing demand for liquid fuels; GM and Ford have both announced they will soon be all electric. This will reduce or eliminate demand for corn-derived fuel ethanol. [That’s] the big opportunity that we have right now: The demise of ethanol would cause us to take a hard look at what we should be doing with this land. Would it be alternative crops? Would it be [to] retire some land from production? Maybe more beef cattle on pasture, things that might generate environmental outcomes better than what we have. But ethanol has got to die.

Do you think it matters that the U.S. doesn’t have a ratified “right” to clean water like the EU?

We’re supposed to have a government for the common good, and we don’t anymore. We have a government for money interests. What we do have is a moral expectation that our leaders will do things to improve the condition. I think, as citizens, we have the right to expect better.

Get the latest food news, from FoodPrint.

By subscribing to communications from FoodPrint, you are agreeing to receive emails from us. We promise not to email you too often or sell your information.

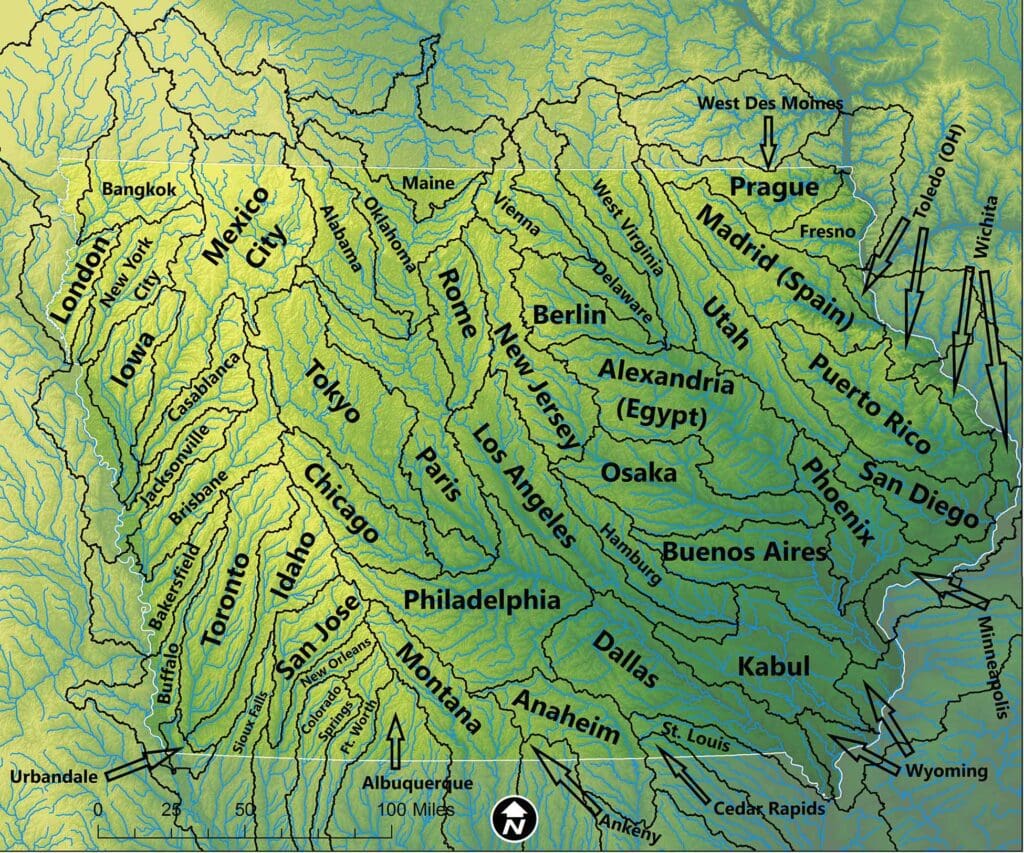

Top map courtesy of Chris Jones.

More Reading

RFK Jr. pushes to close a food additive loophole – but is a gutted FDA up to the task?

April 14, 2025

Our latest podcast episode on pistachios: The making of a food trend

April 1, 2025

Americans love olive oil. Why doesn't the U.S. produce more of it?

February 28, 2025

Finding a pet food that aligns with your values

February 11, 2025

The EPA finally acknowledged the risks of PFAS in sewage sludge. What’s next?

February 10, 2025

How refrigeration transformed our palates and our supply chain

January 28, 2025

The truth about raw milk

January 24, 2025

The environmental benefits — and limitations — of hunting as a food source

January 6, 2025

What to expect in food & farm news in 2025

December 24, 2024

Can sail freight tackle the large carbon footprint of food transport?

December 17, 2024