300 million male chicks are killed every year. Can in-ovo sexing change that?

In mid-July of 2025, a never-before-seen product in the U.S. hit a select few grocery stores for the first time: eggs laid by hens hatched with in-ovo sexing technology.

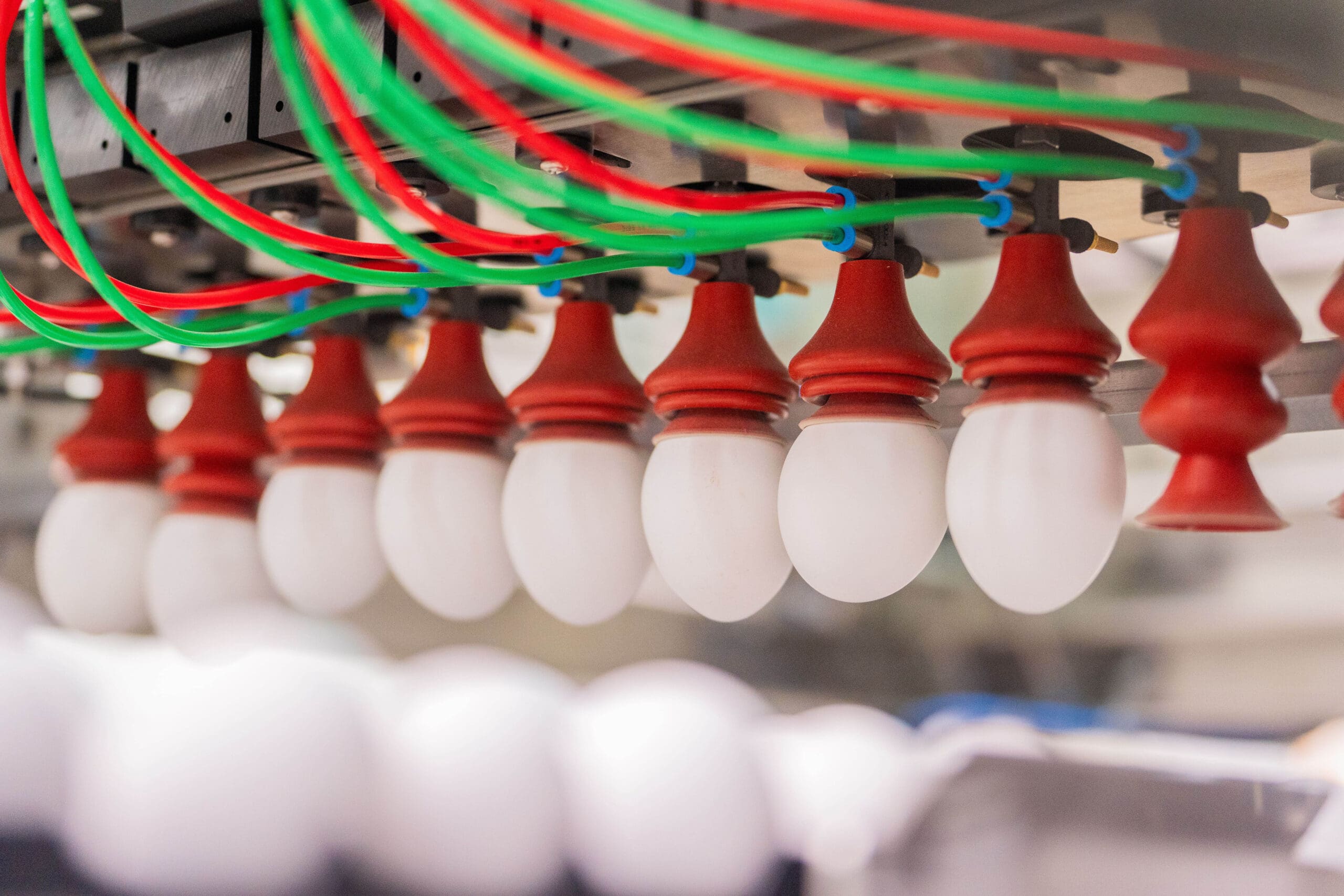

This technology detects the sex of chicks while they’re still in their egg (“in ovo” is a Latin phrase meaning “within the egg”). It’s a revolutionary step for animal welfare when compared to the current practice, which involves raising both male and female eggs until they hatch and then “sexing” them. Farm workers trained to detect minute differences in wing shape and genitalia manually sort the females, who are raised to be egg-laying hens, from the males.

Once sorted, the day-old male chicks are killed using a high-speed grinder that grinds them alive. More than 300 million male chicks are killed every year through this process. Some hatcheries use the chicks for animal feed, but overall their deaths are considered an unavoidable byproduct of egg production.

Now, there might finally be an alternative to this decades-long practice.

In December of 2024, the California-based egg company NestFresh hatched their first all-female flock of in-ovo sexed chicks. Seven months later, the company packaged up the country’s first eggs produced from these chickens.

The eggs were distributed to Whole Foods grocery stores in Arizona, California, Florida and Nevada, with a new label on the carton that says “humanely hatched” — in other words, produced without euthanizing the male chicks, a practice the industry calls “culling.” NestFresh worked with the nonprofit organization Certified Humane to create this new label, which requires a third-party inspector to visit the hatchery to verify they are not culling male chicks. Jasen Urena, vice president of NestFresh, says this was a special moment not just because they were the first American company to offer these eggs, but because it took so many different groups working together over the course of three years to make it happen.

“We’re a producer and we’re a marketer and a distributor, but we’re not a technology company and we’re not a hatchery and we’re not an auditor,” Urena says. “So it took all of those different groups to come together to say, ‘Yes, we can do this,’ or ‘Yes, we believe in this,’ to actually make it happen.”

By the end of September of 2025, NestFresh’s humanely hatched eggs will be in 90 percent of Whole Foods stores nationwide.

Employing in-ovo sexing technology in the U.S. has been a long time coming. The technology is already used in the European Union, where approximately one-third of all egg products sold come from hens hatched with in-ovo sexing.

But in the U.S. progress has been slowgoing, in part because of how many eggs Americans eat: close to 100 billion eggs per year, or about 288 per person.

“The technology that was being utilized [in Europe] just wasn’t big enough,” Urena says. “It wasn’t scalable enough to be used for the industry here in the U.S. where we consume a lot more eggs per capita than the European countries, and our farms and our hatcheries are much bigger here than they are in Europe.”

Another industry expert says the hesitation to adopt this technology in the U.S. could also be because of the highly pathogenic avian influenza, otherwise known as bird flu, that started spreading in chicken flocks throughout the country in 2023.

“Bird flu is a big problem in the poultry industry right now, and it’s one that has kind of caused the egg industry to be very cautious about anything that could impact pricing,” says Hunter Lewis, a product marketing manager for Orbem, one of the companies developing in-ovo sexing technology.

The company uses contactless, AI-integrated MRI scanning to detect the sex of chicks while they’re still in-ovo; it has less than a 2 percent error rate, according to the company. The male eggs are removed from the incubators and destroyed, while the females are hatched. There is potential to move the discarded eggs into a separate market like pet food, but as is the case with the day-old male chicks, the industry does not use these for anything within the human food supply.

Orbem is one of several in-ovo sexing technology companies that started in Europe and is expanding to the U.S., including Cheggy, which NestFresh collaborated with to produce their eggs.

While the technology has gotten cheaper as more companies enter the industry, in-ovo sexing is still more costly than conventional practices, especially during the implementation stage.

But if U.S. prices follow the same pattern as they did in Europe, it’s not a cost that should significantly affect consumer prices.

The use of in-ovo-produced eggs increased prices between 1 and 3 cents per egg, according to a study on the European rollout from the think tank Innovate Animal Ag. That’s 12 to 36 cents per dozen.

Lewis thinks getting in-ovo sexing off the ground could be easier than other major changes to the U.S. egg industry in recent years, like cage-free standards; those have become more widespread with laws like California’s Proposition 12, which banned the confinement of egg-laying hens in 2018. Adoption of those standards required broader participation across the egg industry, from hatcheries to producers.

Because there are far fewer hatcheries than egg producers in the U.S., Lewis hypothesizes that in-ovo sexing technology could be simpler to implement than cage-free because there are fewer players who would need to make the change.

“The only ones who really need to make any changes are the hatcheries, which service most of the egg producers in the country,” Lewis says. Consumer behavior could also help — if consumers are even aware of male chick culling.

A 2023 survey of more than 1,000 U.S. adults commissioned by Innovate Animal Ag found that just 11 percent of consumers know what happens to male chicks once they’re hatched. Forty-eight percent thought they were raised for meat.

But in the poultry industry, there are two types of chickens: laying hens (female) raised for their eggs and broiler chickens (female and male) raised for their meat. Broiler chickens are bred to gain weight quickly, with the fastest-growing ones slaughtered just 5 to 6 weeks after they’re born. Chickens that are bred for the egg industry grow more slowly and are much smaller, which is why the male chicks are not raised for their meat — they can’t reach the same size as broiler chickens.

Once consumers learned about male chick culling, more than half of those surveyed said they were uncomfortable with the process, and nearly three-quarters said the egg industry should find an alternative solution.

“The egg industry really has an opportunity to right this wrong, but whether or not the solution takes hold here in the U.S. relies on customers being ready to buy these eggs."

Nancy Roulston, senior director of corporate policy and animal science at the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA), said consumer behavior is a driving force for popularizing in-ovo sexing technology.

“The egg industry really has an opportunity to right this wrong, but whether or not the solution takes hold here in the U.S. relies on customers being ready to buy these eggs,” Roulston said.

The ASPCA was one of the biggest supporters of NestFresh’s efforts to sell “humanely hatched” eggs, which will expand from pasture-raised eggs to free-range eggs later this year. “If the public can choose these eggs without male chick culling, it will send a powerful message to the egg industry that this issue matters,” Roulston said.

While the eggs are currently only available in Whole Foods, other retailers could soon join them.

Earlier this year, Walmart released its animal welfare policies and included “gendering innovation” as a focus area for its egg-laying hens. While not an outright commitment to begin stocking eggs produced with in-ovo sexing technology, animal welfare experts say it’s a welcome sign of forward momentum on this issue.

“I think that in-ovo sexed chicks can definitely be the next wave of animal welfare, like cage-free was 20 years ago,” Urena says.

Get the latest food news from FoodPrint.

By subscribing to communications from FoodPrint, you are agreeing to receive emails from us. We promise not to email you too often or sell your information.

Top photo by wanessa_p/Adobe Stock.

More Reading

What do faster line speeds in slaughterhouses mean for animals, workers and food safety?

May 8, 2025

When "Made in America" isn't really: Country-of-origin labeling for beef

May 8, 2025

This vegan tiramisu will bring you joy

March 11, 2025

Finding a pet food that aligns with your values

February 11, 2025

The environmental benefits — and limitations — of hunting as a food source

January 6, 2025

The USDA updated label guidelines to increase transparency — is it enough?

September 12, 2024

How can ecofeminism help us envision the future of food?

July 18, 2024

Switching from beef to chicken isn't the sustainability flex you think it is

June 12, 2024

Is it too cruel to eat veal, foie gras and octopus?

May 14, 2024