Is the Chocolate Industry Doing Enough to End Exploitation?

For Valentine’s Day 2019, Americans spent $1.8 billion on candy, a good chunk of which went to the purchase of 36 million heart-shaped boxes of chocolate. These feel-good purchases of the earthy-sweet and delicious stuff [unbiased author opinion] are meant to convey love and devotion — possibly due to the fact that chocolate contains phenylethylamine, a brain chemical associated with feelings of euphoria, according to food historian Alan Davidson — but they have a dirty secret. Since Europeans first got their hands on it way back in the 16th century and began to cultivate its tree-of-origin, cacao, chocolate has been synonymous in practice, if not always in common knowledge, with the exploitation of peoples and the degradation of land. As the chocolate industry has grown over the centuries so, too, have the scope and scale of the abuses.

The Chocolate Industry Is Trying to Solve the Problem

This chocolate/exploitation link is a connection that the 21st century chocolate industry is desperately trying to break, with varying levels of success. Its efforts are scrutinized by increasingly alarmed consumers who would like to spend their chocolate dollars in support of companies that promise a product that does not use child labor or contribute to deforestation, and that pays a living wage to its farmers; they also look for these claims to be backed up with third party certification.

The Shortcomings of Certifications

Social and climate justice non-profit Green America devised an annual scorecard to rate chocolate companies’ successes in these areas. (And they’ve just released a brand new scorecard that rates supermarket and drugstore “own brands.”) But “when we first started [about 5 years ago], the general movement wasn’t aware of the shortcomings of certification,” says labor justice campaign manager Charlotte Tate — an issue we’ll elucidate below. “There’s since been an understanding that certification can’t solve all this, and some companies with ratings are doing meaningful projects and programs outside of that certification that, from, our perspective get at the core of the issue.

Oversight of the Chocolate Industry is Difficult

How far has the industry come in its “meaningful” work, and how far does it still have to go in creating humane and ecologically sustainable treats? It’s hard to say for sure.

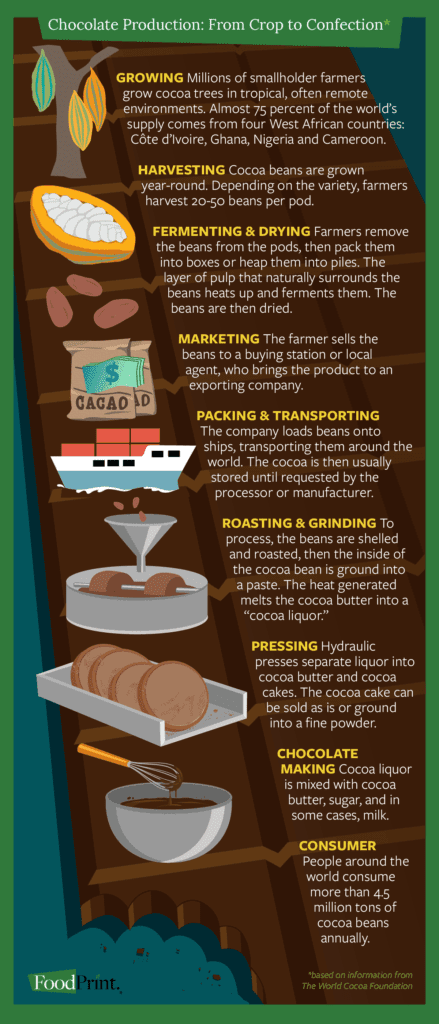

The chocolate supply chain is intensely complicated, and adding to that complication is the fact that cacao itself is different from other commodities in that “it is not farmed on huge, accessible plantations but comes from millions of small-holder farmers, often working in remote areas,” making oversight difficult, according to Alexander Ferguson, vice president of communications for the industry trade group World Cocoa Foundation (WCF). There was also a general reluctance among relevant actors contacted for this story to speak on the record, if at all.

But if you’re interested in how the chocolate industry got to where it is now, how it’s trying to dig out, and what that means for your own attempts to be a conscientious binge-eater, read on.

A Short History of Chocolate

Almost 75 percent of the world’s supply of cacao comes from four countries in West Africa: Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Nigeria, and Cameroon. But the tropical, shade-loving evergreen is native to Central and South America thousands of miles away. The first people we know of to eat chocolate — or rather, drink it; it was consumed as a beverage only for 3,000 years or longer — were the Olmecs, who inhabited the Gulf Coast region of today’s Mexico between 1500 and 400 BCE. Their near-worship of cacao was adopted by the Maya and the Aztecs, who mixed it with a variety of herb, flower, and corn flavorings and used it as a ceremonial drink.

The Spanish got a hold of cacao in the 16th century as they were conquering their way through the Yucatan. They gave it a new name, from the Mayan word for “hot,” chocol, and the Nahautl word for “water,” atl; and turned it into an object of international trade and societal passion. And of course, that’s when the trouble really began.

With Chocolate’s Popularity Came Human and Environmental Exploitation

As the craze for chocolate swept across Europe, it picked up sugar as an additive and also started appearing — mixed with cocoa butter and/or milk — in the form of pastilles and other munchable, rather than slurpable, goodies. There was a dark side to chocolate’s increasing popularity: the slave labor used to grow cacao for export first in Latin America, then in the West Indies, then in West Africa by the 19th century, and in parts of Asia by the 20th. Wherever the burgeoning business landed, once-lush forests were cut down to make way for cacao plantations. And of course, as has been widely reported, these issues exist in cacao (or cocoa) production to this day. They’re exacerbated by low wages that keep farmers in poverty — often leading them to cut down trees and use their children to help with the crop. It’s poverty, says Ferguson, that is “the central challenge to solving problems in the cocoa supply chain.”

Reckoning With Chocolate and Child Labor

In 2001, the use of child labor in the cocoa business — both in the form of trafficked children and those working for free for their families — became a “cause célèbre” of the US Senator Tom Harkin and Representative Eliot Engel, who negotiated the voluntary Harkin-Engel Protocol with the cocoa industry to track and reduce the worst of these abuses, as Fortune reported back in 2016. The enterprise failed miserably, with millions of children still working even today, in dangerous conditions. Ongoing media investigations found that in some cases, the problem was getting worse. This in spite of an industry-wide attempt to reform: hundreds of millions of dollars invested in antipoverty programs and the forming of anti-child-slavery, company-funded nonprofits like the International Cocoa Initiative (ICI).

Chocolate and Deforestation

Another bombshell dropped in 2009, when reports of “epochal” deforestation started to appear. Not only was the chocolate industry singlehandedly driving the destruction of forests in West Africa — 2.3 million hectares just in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana between 1988 and 2007; they were also purchasing cacao that had been illegally grown and harvested in protected national forests and parks. In October of this past year, the Washington Post ran a piece with the damning sub-headline: “A decade after Mars and other chocolate makers vowed to stop rampant deforestation, the problem has gotten worse.” And another scandal, also reported by the Washington Post that same month: Dutch auditing organization Utz, which oversaw certification for fair labor and forestry standards, had been giving non-compliant actors in both categories a pass.

At the Root of Chocolate’s Problems, Poverty

Says Tate, “Cocoa shouldn’t be as cheap as it is. Farmers need to be paid more than a living income so can they save, not just be worried about their own survival.”

Indeed, poverty is now largely understood by stakeholders to be the number one root of chocolate’s woes and those woes it engenders, and there have been steps taken to address it. WCF’s 100 members — chocolate companies, farmers, banks, and others along the supply chain — partner with governments and other organizations to promote a range of potential fixes.

Solutions to Chocolate’s Problems

One of these is making farms more profitable with diversification — the planting of crops and shade trees beyond cacao “that farmers can sell and use to feed themselves,” says Ferguson. Another is an agreement with the governments of Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana to pay a living wage differential so farmers can earn more for their harvests, and to commit, along with 34 chocolate companies, to halting the conversion of forest land to cocoa production. Ferguson says ICI has had some success in mitigating child labor, by implementing community development projects, including building and maintaining schools. But “It’s going to take persistence, the continued commitment of governments, companies, communities, and society, to get progress,” he says.

"Cocoa shouldn’t be as cheap as it is. Farmers need to be paid more than a living income so can they save, not just be worried about their own survival."

Transparency and Traceability

Green America advocates for full traceability throughout the supply chain; Dutch company Tony’s Chocolonely, which scores an A rating, has made theirs public. Smaller companies like this one have a leg up in addressing labor and deforestation issues, says Tate, because larger companies “have a [long-standing] business model set up and now have to react” to reports of abuses. Whereas small companies “have arisen because they saw problems in cocoa and wanted to produce ethical chocolate in a more proactive space.” She says such companies often also have stronger relationships with their farmers so they know what they need “and aren’t just guessing from the other side of the world.”

Transparency is still needed when it comes to certifications, and some organizations are notifying consumers about their processes. For example, the Utz certification scandal prompted Fairtrade International to elucidate how its auditor, FLOCERT, addresses supply chain challenges like deforestation and child labor. Meanwhile, it continues to make the focus of its work paying farmers a fair price, it asserted in an emailed response to FoodPrint, setting a minimum price of $2,400 per metric ton of conventional cocoa. It also pays a premium to cooperatives that sell cocoa according to its terms.

Co-ops, says Tate, can be a good way to help farmers make a decent living. She says Divine Chocolate is majority co-op-owned, with farmers given a seat at the decision-making table. Theo Chocolates does not operate on a co-op model, but Tate says they’re still committed to providing higher wages for those who work on its behalf. That can translate into a bit more cash spent at the supermarket checkout — $4 for a 3 oz. bar of Theo compared to $2 or $3 for a 4.4 oz. bar of Hershey’s or Lindt, for example. It’s also possible you could notice an increase in price for big brand chocolate bars whose companies have similarly committed to boosting wages for their farmers. Your extra dollars and cents help ensure that a gift intended to express your love to your partners shows equal care for workers and our planet.

Big Chocolate Companies Have a Reckoning

Ferguson says larger companies are making positive strides on the environmental side of things as well; Switzerland’s Barry Callebaut, for example, which was implicated in the purchase of chocolate from illegally deforested West African parks, is now making progress reports on traceability publicly available, as is M&Ms maker Mars. But he says continued work between partners has to be fostered long term.

Tate agrees that strong, ongoing partnerships are vital to improving the industry. But “I hope consumers know how much power they have. The media covering [these abuses] this year has been great for awareness-raising. Companies know we’re watching.”

Get the latest food news, from FoodPrint.

More Reading

MAHA wants to reform food, health and scientific systems — why is it ignoring nitrates?

December 18, 2025

From goldenseal to reishi, what is the true cost of the wellness industry's obsession with wild foods?

December 2, 2025

The invisible immigrant labor sustaining America’s chicken obsession

October 21, 2025

Can extended producer responsibility programs push food companies to use sustainable packaging?

October 16, 2025

The meat industry smeared the Planetary Health Diet. Now its creators are back with more evidence.

October 10, 2025

300 million male chicks are killed every year. Can in-ovo sexing change that?

September 30, 2025

How to avoid eating microplastics and chemicals in plastic

September 25, 2025

For these cocoa farmers, sustainability and the price of beans are linked

September 17, 2025

Salmon hatcheries: Unsuccessful conservation, insufficient regulation, and poor animal welfare

September 16, 2025

Can recycled soil blends support a more sustainable future?

September 5, 2025