The never-ending seed oil debate

In quick succession, the second Trump administration has slashed supports for infectious disease and disaster response, affordable prescription drug access, public health research, clean water, clean air and fresh local food for school meals and food banks. Meanwhile, its secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., has decided Americans’ health is best achieved by pushing (risky) raw milk consumption and vaccine skepticism (in the middle of a measles outbreak), and banning food dyes and seed oils. He “does not follow scientific evidence,” one medical professional told “Scientific American,” echoing criticism from pretty much every corner of the scientific community.

These and many other of Kennedy’s Make America Healthy Again (MAHA) pursuits have already been soundly debunked by scientists and media outlets alike. Still, the seed oil chatter continues apace — with social media influencers spouting a myriad of misinformation linking seed oils to cancer and heart disease and diabetes; wellness spinoff sites like Goop Kitchen (often erroneously) proclaiming themselves seed-oil free; healthy fast-casual chains like Sweetgreen offering a seed-oil free menu; and a new certification scheme for packaged goods companies dropping from the Seed Oil Free Alliance, which calls ingestion of seed oils a matter of “high concern” despite a lack of corresponding evidence. Should you be avoiding seed oils? Nutrition scientists are clear that this sort of reductionist approach to what we eat is unhelpful and potentially detrimental to our health. For those who can afford it, they recommend a balanced diet rich in whole foods and produce with everything else — seed oils included — perfectly fine to consume in moderation. Below, FoodPrint dives into the science.

What is a seed oil?

The definition is simple: an oil made from plant seeds like sesame, sunflower, safflower, rapeseed (a.k.a. canola, a portmanteau of CANadian Oil Low Acid), grapeseed, pumpkin, rice bran, cottonseed, soybean, peanut and corn. MAHA types and wellness influencers refer to a subset of these — subtract sesame, grapeseed and peanut from the list above — as the “Hateful Eight.” Oils that are not made from seeds but rather from fruits are olive, avocado, palm and coconut.

How seed oils are made

Once upon a time, our cooking fats were limited to those we could obtain with rudimentary tools: butter churned from the milk of ruminants; tallow, lard and schmaltz rendered from the cows, pigs and chickens, respectively, whose meat we ate; oil mechanically squeezed from olives and sesame seeds. “These were expensive, oils were dear,” says James Curley, a natural food industry consultant who publishes a Substack as the Natural Foods Geezer.

About 100 years ago, the food industry figured out how to get oils from cheaper, more abundant seed sources that are now largely grown in industrial monocultures. Since many of them are not actually that oily, industrial extraction is necessary to get high oil yields. That extraction relies on a chemical process that uses a crude oil-derived compound called hexane to act as a solvent: It breaks open seed cells and pulls the maximum amount of oil from them.

This is not the only way to get oil from seeds; they can be mechanically squeezed (i.e. expeller-pressed), too. Non-chemically derived sesame oil — a product that’s been made and consumed without health incident for thousands of years — can currently be bought in almost any supermarket; mechanically pressed sunflower, safflower and canola oils are available, too, from brands like Spectrum. For this reason, Curley makes a distinction between any oils from any seeds, and those that are solvent-derived; he refers to the latter as Industrially Extracted Vegetable Oils, or IEVOs, and these, he says, are what the anti-seed oil contingent is actually railing against. That’s how you get Goop Kitchen, for example, claiming to be seed-oil free when it lists sesame oil in its cooking ingredients.

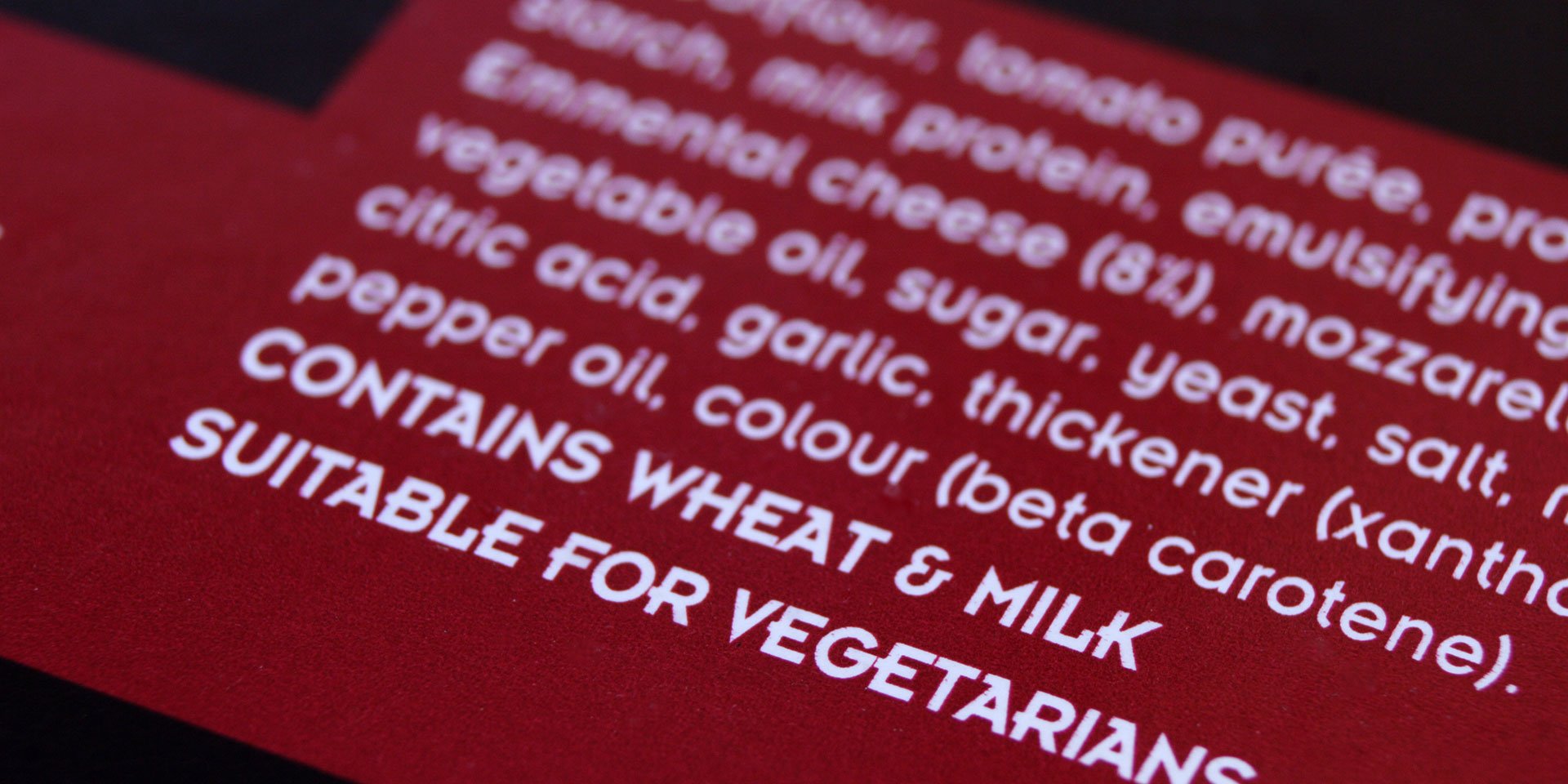

In the 1980s, oils of concern were hydrogenated — they used hydrogen gas to make products such as margarine from corn and soy. These are high in trans fats, which raise LDL (bad) cholesterol levels; this is partly why industry switched to hexane-extracted seed oils, which have low to no trans fats. Although the bottle of Crisco or Wesson you buy at the supermarket is a (likely soy-based) seed oil, Americans are mostly consuming these inexpensive fats when they eat ultraprocessed foods (UPFs). As Curley explains, “Everything from Ritz crackers to Oreos — anything that gets high-speed processed and run through mixers, extruders, depositors, band ovens — uses those oils in quantity because they make the dough more pliable.” If you eat a lot of fried fast food, you’re getting a good dose of these seed oils there, too.

The health claims vs. what the evidence says

The anti-seed oil brigade has made loud claims that these products are toxic for humans to eat, because they rely on an industrial process that alters their chemical makeup and allows traces of dangerous hexane to potentially enter our bodies. They’ve backed up their claims with studies that show all kinds of unhealthful effects — studies that Jera Zhang, a nutrition professor at Hunter College in New York, says are too tiny, or too reliant on mice (versus human) subjects to be conclusive. “People are always looking for a clear, straightforward, black-and-white answer — is it good or bad?” she says. “That’s not how nutrition works.”

Empty calories

There are four main concerns that the Seed Oil Free Alliance and other MAHA-ites cite when it comes to the oils’ purported negative health effects. The first concern is that seed oils provide empty calories, similar to refined sugar. Some would like to see fruit oils such as avocado, olive, coconut and palm oil replace seed oils — even as some of them outright admit that a global supply chain does not exist that would allow big brands to completely swap out their seed oils for fruit oils. Such a swap would also be extremely costly for the makers of consumer packaged goods — as well as baby formula companies, which Kennedy has recently tried to convince to divest of seed oils. Points out Jessica Wilson, a dietician with a podcast called “Making It Awkward,” “People are already stealing formula because they need it and it’s expensive. Making it more expensive with avocado oil or olive oil is terrifying to me.”

“People are already stealing formula because they need it and it’s expensive. Making it more expensive with avocado oil or olive oil is terrifying to me.”

Kennedy and a host of wellness influencers propose eating tallow instead of seed oils in many scenarios, often claiming that it is a good source of Vitamins A, D, E and K, despite supplying very few of these nutrients per calorie. Although the occasional fast food chain might go along, vegans and vegetarians won’t eat foods fried in an animal by-product. Additionally, like butter — and as Zhang points out, coconut oil — tallow is high in saturated fat that can raise LDL levels and build up plaque inside arteries. A little of any of this is okay, says Curley. “But people make the leap [that] if seed oils are bad, suddenly tallow is good for you. All they want to do is continue their bad habits” of eating unhealthful ultraprocessed snack foods. (He says they also fail to make the connection that the same seeds in oils feed the cattle that gave up the tallow in the very same industrialized system.) Zhang is quick to point out that cardiovascular disease is the number-one killer of Americans. Many, many years of studies on human subjects have shown conclusively that a higher intake of saturated fat from animal fats “is bad for cholesterol and triglycerides and also increases the risk for cardiovascular disease significantly. There’s just so much evidence that we can be really confident about,” she says, adding, “I would never recommend lard to be a major part of one’s diet.”

Aldehydes

The second MAHA claim is that seed oils form volatile compounds called aldehydes, which they insist are toxic. Studies have linked aldehydes to an increased risk of cancer and cardiovascular disease — although most of these center on the inhalation of aldehydes in their gas form, not on consumption of them, which is an important distinction. And they implicate high-frying temperatures in places like fast food restaurants, as well as frying oil that’s used over and over, which are things to avoid no matter the cooking fat.

Nutritionists are more worried about high consumption of fast foods and ultraprocessed foods, especially if there’s a concurrent lack of nutrient-dense whole foods in a person’s diet. “I have had my patients tell me they are not going to eat baby carrots or celery unless they have ranch dressing” that’s probably made with seed oil, says Wilson. “And I’m like, yes, let’s do that. Getting antioxidants and fiber is far more my goal than looking at the minutia of what’s in ranch dressing. I am less concerned about what is there versus what’s not there” — namely, healthy proteins, fruits and vegetables.

Says Zhang, “I care more about the context. If we’re talking about seed oil in fast food, fried food or ultraprocessed food, that’s a kind of food we want to avoid.” She adds, “It’s not because of the seed oil; it’s because [this food] is not nutrient dense.”

Omega-6s and inflammation

The third big anti-seed oil concern relates to inflammation. This has to do with fatty acids — in particular, omega-6s, which naturally occur in foods like walnuts and almonds, eggs and some of the seeds used to make oils. Your body needs omega-6s, just as it needs the omega-3s that come from eating fatty fish, beans and (again) seeds; omega-6s boost your “good” cholesterol and omega-3s reduce inflammation.

However, research associates a long-term diet high in omega-6 fats specifically from soybean oil (versus a diet heavy on palm oil) with a disruption of the gut microbiome that leads to intestinal inflammation. This has led some in the anti-seed oil camp to make a more sweeping indictment against all seed oils, and to say the resulting imbalance between inflammation-causing omega-6s and inflammation-mitigating omega-3s warrants cutting out seed oils altogether. Many in the nutritionist camp say eating more omega-3s — and just more whole foods — will do the trick. Zhang, though, believes that pegging omega-6s as inflammatory is “naïve.” Our body metabolizes omega-6s into all kinds of things — some inflammatory, some actually anti-inflammatory and health-protective, she says. And how, exactly, would one determine if they’d over-eaten omega 6s?

Hexane residues

There’s a fourth popular anti-seed oil concern: hexane residues. On her Instagram page, wellness influencer The Food Babe raises the alarm about consuming this “dangerous neurotoxin.” However, nutrition scientists, in a report from “The Guardian”, affirm that hexane is virtually eliminated from hexane-derived seed oils through the refining process. In fact, it’s difficult to find a reputable report that does not present overwhelming scientific evidence in support of seed oils — especially as an alternative to animal fats. If consumers remain concerned about ingesting seed oils, they can opt to eat fewer ultraprocessed foods and purchase expeller-pressed oils for their home kitchens.

The real issue

Implicating seed oils in bad health consequences is not a one-size-fits-all proposition. Especially since the overwhelming balance of evidence affirms that consuming seed oils over other fats is associated with better cardiovascular health in particular.

Regardless, the Seed Oil Free Alliance certification is already making its way onto product labels. One natural food store owner says his customers avoid seed oils at all costs, but more as a soapbox against our industrialized food system, over which consumers feel powerless. He mentions an essential irony: MAHA influencers reject seed oils but push supplements like fish oil that are chemically derived in the same way refined seed oils are.

“If we take in such a reductionist approach to science and what the research shows … what we’re left with is something that's based on little science but a lot of misunderstanding and misinformation.”

Demonizing seed oils is a distraction from the much larger issues at play, say nutritionists. When we talk about UPFs, we could pick out salt as the problem, or sugar, or emulsifiers. Focusing on refined seed oils “sounds sciencier,” says Wilson, while also eroding belief in the real nutrition science out there. Similarly, nitpicking about which part of our body is negatively affected by seed oils is a red herring. A study that says, “Lard is good for the microbiome — well, what about heart health and disease risk?” says Zhang. “The microbiome is just one part of health.” If we have an overall healthy eating pattern, she says, “there’s no reason to see seed oil as evil.” As University of California, Davis, food scientist Selina Wang said on a recent podcast with Wilson, “If we take in such a reductionist approach to science and what the research shows … what we’re left with is something that’s based on little science but a lot of misunderstanding and misinformation.”

Curley is more peeved by what he calls the “me versus we” divide in wellness circles, with MAHA influencers focusing on individual health in end products. This at the expense of a more holistic look at the industrialized food system that’s delivering alarming rates of pesticide exposure, poor dietary choices for under-resourced people, and wholesale environmental degradation. He offers an analogy using tomatoes — one organic, one conventional. “People are like, which one is better? And I’m like, the organic tomato,” he says. “Why, is it higher in Vitamin C? No. Is it higher [in] lutein? No. Is it higher in antioxidants? No. Why is it better? Because this organic tomato was grown in a system that puts something back into the system, into the soil, into the preservation of tomatoes for my great-grandchildren. The other tomato was grown in an extractive environment where nothing is put back. Are seed oils bad for me? That’s not the point. Seed oils are industrially extracted. Seed oils are bad for the environment. They’re bad for the long-term health of food systems. Where’s that thread?”

Get the latest food news from FoodPrint.

By subscribing to communications from FoodPrint, you are agreeing to receive emails from us. We promise not to email you too often or sell your information.

Top photo by sarymsakov.com/Adobe Stock.

More Reading

A new book says tech-supported industrial ag will feed the world. Agroecologists would like a word.

July 9, 2025

Whey too much: The hidden costs of the protein boom

May 29, 2025

Beyond honeybees: The benefits of pollinator diversity

May 28, 2025

Big Banana’s bitter labor truths

May 13, 2025

What do faster line speeds in slaughterhouses mean for animals, workers and food safety?

May 8, 2025

When "Made in America" isn't really: Country-of-origin labeling for beef

May 8, 2025

RFK Jr. pushes to close a food additive loophole – but is a gutted FDA up to the task?

April 14, 2025

Our latest podcast episode on pistachios: The making of a food trend

April 1, 2025

Americans love olive oil. Why doesn't the U.S. produce more of it?

February 28, 2025