How are ultraprocessed foods defined? A new California bill aims to decide

In 2009, Brazilian epidemiologist Carlos Monteiro and his team of researchers at the University of São Paulo released their Nova Food Processing Classification System. This sorted foods into categories related to how they were altered before they arrived on a dinner plate: 1 for fresh foods; 2 for foods that were milled or ground or dried or pressed; 3 for foods that got fermented, canned, smoked, pickled or cured; and 4 for foods that were chemically modified somehow — what we now refer to as ultraprocessed foods (UPFs).

The freak-outs and confusion kicked in almost immediately and never abated. Food industry reps protested what they claimed was “flawed science.” Media reported the both-sides-ism of ensuing health debates, clarifying little. Nutritionists got flummoxed over how to classify plain yogurt: Was it category 1, as Nova labeled it? Was it category 3, for its fermentation process? Or was it category 4, for its naturally occurring whey and casein, which Nova deemed industrial ingredients (in other instances, they can be)?

“There’s a difference in levels of processing, but Nova doesn’t make any distinction” about metrics like nutrient-density, says Michael Hansen, Senior Scientist at Consumer Reports. Meaning, those classifications don’t tell us much about the nutritional pros and cons of a category-4 UPF: A container of chickpea hummus with an added stabilizer and a can of all-artificial soda both qualify, for example.

In the intervening years, a lot of research has linked the high-sugar, -salt, -fat, -calorie counts in some of these highly processed comestibles to cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and depression; to excess calorie intake, weight gain and obesity; and, potentially, to addictive behaviors. There’s been additional work to tease out which UPF additives might give the greatest causes for concern: Synthetic dyes have been associated with behavioral issues in some children, and French researchers linked a slew of emulsifiers to increased cancer risk. Meanwhile, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. insists on the toxicity of seed oils, a common ingredient in UPFs, despite a dearth of scientific evidence.

In the absence of useful federal guidance on UPFs — a discredited Make America Great Again (MAHA) report contained fabricated and inaccurate citations — states are recognizing that the onus to protect consumers from hazardous food chemicals lies, now, with them. The standout is California, which has pending legislation that would scientifically define, maybe for the first time, according to Hansen, what a UPF actually is. He hopes the state’s precision in defining UPFs, and its commitment to figuring out which of them are the most harmful, will provide a roadmap for other states seeking to get hazardous chemicals out of foods, starting with those fed to kids.

More than an ingredient list

As of June 2025, seven states had passed nine bills related to food additives — these out of 93 bills introduced in 35 states. Most of them are aimed at dyes and additives in school meals, although which dyes and additives differ. Virginia also targets metals in baby foods. Texas passed a law to put warning labels on foods containing all nine synthetic dyes targeted by RFK Jr. for voluntary industry phase-out, along with bleached flour, partially hydrogenated oils and various preservatives — additives the label must state have been banned or unapproved elsewhere (Hansen says not every ingredient on the list falls into those categories, however). “This is just a list of chemicals they came up with,” he says dismissively; he believes the wording on the labels could be challenged on First Amendment grounds.

“To see all of these regulations come out using wildly different and scientifically unsubstantiated definitions of ultraprocessed foods has been completely baffling. It seems like they're all just making up their own definition."

“To see all of these regulations come out using wildly different and scientifically unsubstantiated definitions of ultraprocessed foods has been completely baffling. It seems like they’re all just making up their own definition,” says Lindsey Smith Taillie, a nutrition epidemiologist at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, who has participated in conversations with California about how to define UPFs. No nutritionist is “opposed to removing artificial colors, but you can take the artificial color out of an ultraprocessed food, replace it with a natural color, and it’s still going to be an ultraprocessed food.” She’s more concerned with creating nutrient profile models for foods that consider processing methods and nutrients that should be eaten in moderation (sodium, sugar, saturated fat), along with other ingredients.

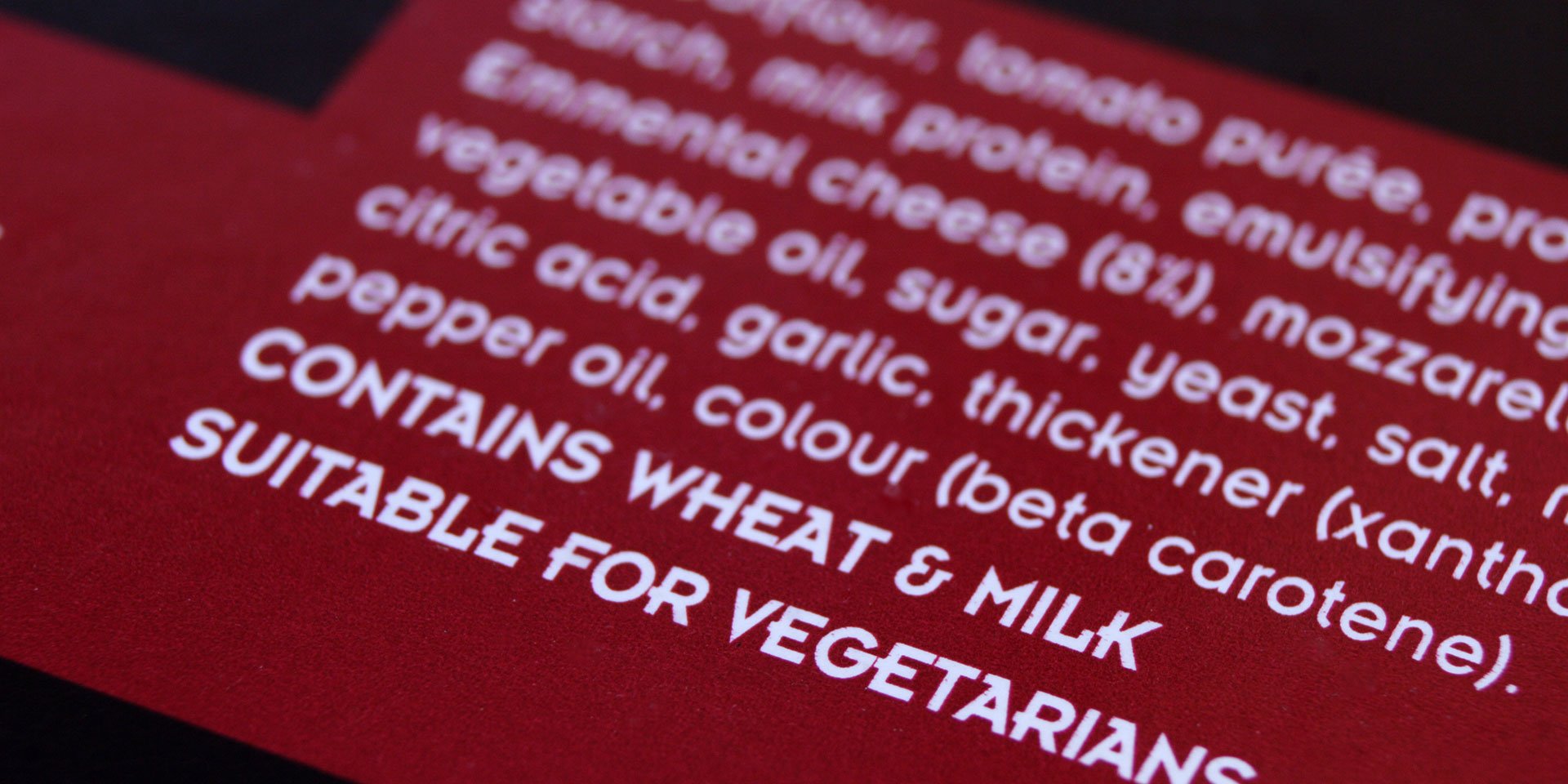

For its part, California has been systematically trying to improve the quality of the meals its public schools serve. In 2023 it banned Red Dye No. 3, propylparaben (an endocrine disruptor), brominated vegetable oil (linked to thyroid toxicity; FDA banned it a year later) and potassium bromate (a carcinogen) from school foods; it followed up in 2024 by banning six dyes. Its newest bill, which passed the Assembly and is awaiting consideration by the Senate, would define a UPF as a food that contains any of nine categories of additives: surfactants; stabilizers and thickeners; propellants, aerating agents and gases; coloring agents; emulsifiers; flavoring agents; flavor enhancers; surface-finishing agents; and nonnutritive sweeteners. From there, it would task the state’s Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment with determining which of these foods are “particularly harmful” according to current research; these would be phased out and reviewed every two years to accommodate emerging science.

As impactful as this bill would be, Hansen says more work would need to be done to improve the healthfulness of foods that kids are exposed to: by removing corn syrup solids from infant formula (a defined UPF that may predispose infants to obesity); fixing the loophole that allows manufacturers to use ingredients that are “generally regarded as safe” (GRAS) without a safety review from the Food and Drug Administration — New York has been working toward this; tackling environmental contaminants like heavy metals, phthalates, plastics and PFAS in the food supply; and, as the Trump administration slashes funding for farm-to-school initiatives that bring local whole foods into cafeterias, finding ways to keep those healthy food pipelines open. As registered dietician Toby Amidor points out, abolishing ingredients like food dyes “isn’t going to do anything if you don’t eat a well-balanced, varied diet overall.”

Healthy-ish vibes

California’s initiative is an important corrective to a MAHA “clean” eating mindset that often seems to pull more from vibes than science — Smith Taillie calls it “theatrical, a way to claim that they’re doing something while doing nothing.” A hint of opportunism pervades several apps on the market, like Open Food Facts, the Processed-Food Scanner and Yuka, that guide consumer supermarket purchases; they use the Nova classification as their baseline, or a European metric called Nutri-Score that assesses (experts say with varied utility) nutritional value and additives, or a combination of both. One new app, called WISEcode, purports to update and improve the Nova system.

While Richard Black, WISEcode’s chief scientific officer, credits Nova’s Monteiro with “raising the level of awareness of the potential for issues around foods that are heavily processed,” he says WISEcode’s data sets go beyond by identifying “the chunk that is truly problematic for health.” (Dr. Monteiro did not immediately respond to a list of questions about whether Nova’s metrics need refining.) Ingredients are weighted based on level of processing and potential health risk gleaned from existing science; calories from added sugar are calculated, as are ingredients banned in other countries. Foods are organized into five categories, from minimally processed to super-ultraprocessed. When a product is scanned, it generates a color-coded owl icon that ranges from green (Banza Cheddar Elbows mac and cheese) to red (Jimmy Dean Sausage, Egg & Cheese Croissant Sandwiches).

WISEcode plans to add a setting that offers customized suggestions to “nudge people to embrace their own personalized nutrition based on their goals,” Black says — a whiff of MAHA and its health metrics that can skew more toward wellness than science. Current settings let a user select for “sketchy,” “all-natural,” “clean,” and yes, even “MAHA” ingredients. None of these terms are clinically defined, says Amidor, who tried the app — she calls the “sketchy” category “silly” and non-instructive about a product’s quality or healthfulness.

WISEcode’s methodology overlaps with California’s at least somewhat; Black says some of the ingredients California currently calls out would merit a super-ultraprocessed rating. Where they differ, significantly, is in who they mean to serve. WISEcode targets mostly female heads of households aged 25 to 45 in the mid-socioeconomic level, which overlaps pretty neatly with the Goop demographic — namely, people who can afford to be picky about what they eat. California is a state where 27 percent of households with children experience food insecurity, and it serves almost 6 million meals every day in public schools. Moving the needle on nutrition outcomes for the latter demographic — under-resourced families who have less buying power, not to mention time to prepare whole, healthy, scratch ingredients — holds real potential to make lasting, much-needed change.

Get the latest food news from FoodPrint.

By subscribing to communications from FoodPrint, you are agreeing to receive emails from us. We promise not to email you too often or sell your information.

More Reading

What do faster line speeds in slaughterhouses mean for animals, workers and food safety?

May 8, 2025

The never-ending seed oil debate

April 29, 2025

RFK Jr. pushes to close a food additive loophole – but is a gutted FDA up to the task?

April 14, 2025

Can the FDA's new rules help people eat healthier?

March 19, 2025

The EPA finally acknowledged the risks of PFAS in sewage sludge. What’s next?

February 10, 2025

The truth about raw milk

January 24, 2025

Food Is Medicine: the inextricable link between food and health

December 30, 2024

What to know about nonstick cookware

December 6, 2024

How we came to rely on emergency food

September 30, 2024