Published: 7/08/19, Last updated: 3/03/26

Introduction

When you reach for the milk to splash in your coffee, select a slice of cheese for your burger or pick your late-night ice cream treat, you’re presented with a lot of options from organic to grassfed. You’re also faced with many questions about how these products affect your health and what kind of a larger system they’re a part of. Maybe you’ve heard that family dairy farms are going out of business across the country and you want to support them. Or perhaps you’ve just read that article about the lakes of manure at factory farms. And wasn’t your friend just talking about the growth hormones in milk? Do you really want to eat that?

Just about any way you measure it, the U.S. dairy system is in crisis. Most of our milk today does not come from family dairy farms with a few dozen cows grazing on grass, but instead from massive megadairies housing thousands of cows in miserable conditions. Their manure is stored in huge pits that smell terrible and are prone to leak and contaminate the water in surrounding areas. These operations produce so much milk that the price paid to farmers for milk has plummeted far below the cost of production — forcing many small family-run dairy farms out of business and even leading to an increase in the number of farmer suicides.

The system is working out well for the big dairy processing plants that largely control it. But it’s terrible for farmers, workers, dairy cows, the environment — and you, the consumer.

A different system is possible. Milk, cheese, yogurt, ice cream, and the rest can be nutritious and delicious parts of our diet. Family-run dairy farms can be a healthy part of the rural economy and environment. Farmers can get a fair price for their milk, and workers can be paid and treated well on humane farms. Across the country, community residents, farmers and workers are advocating for tools like state policies that curb megadairies and a national supply management program to guarantee a fair price for all farmers. More and more farmers are transitioning to produce grassfed milk, and demand at the grocery story is skyrocketing.

The dairy industry is complicated, but that also means there are many ways in which it could be improved for farmers, workers, animals, the environment and the consumer. In this report we lay out the many problems with the current system (especially its catastrophically large foodprint), while charting a path for how it can be better.

What dairy cows should be

Dairy cows should live in conditions that give maximum consideration to their health and well-being, as well as to that of farmers, workers and the surrounding environment. They should spend most or all of their day grazing on pasture and should be:

- housed at a density where their water use and waste is not a burden on the local environment.

- raised by farmers who are guaranteed a price for their milk to cover their costs of production and by workers who are paid a living wage and treated well.

They should not be:

- given artificial growth hormones.

- pushed to produce at an unhealthy rate that shortens their lifespan.

Milk should:

- Have meaningful and verifiable labels that consumers can easily understand.

- Be nutritious and delicious.

The basics of milk

You put it in your coffee every morning, but how much do you know about where milk actually comes from and how it gets to your table?

What does a dairy farm look like?

The dairy farm pictured on milk and yogurt cartons often features cows grazing on grass, with a red barn in the background. Some milk still comes from farms like this, with cows kept on pasture most of the time, coming indoors only to be milked or in bad weather. But the majority of milk today instead comes from huge megadairies housing tens of thousands of cows confined in a huge barn or on a dry lot, with no access to vegetation.

In between the all-pasture farm and the megadairies are many family-run farms with a few hundred cows, which generally house their cows in free-stall barns, where the animals can move around, feed and lie down as they like. Many of these also give their animals some access to pasture — most often to heifers or dry cows, since they do not need to be brought to the barn for milking. According to a 2014 survey, 60 percent of farms gave access to pasture to milking cows and more than 70 percent gave pasture access to dry cows, with smaller farms more likely to give pasture access.1 These mid-size farms generally grow some of their own feed, including hay, corn or soybeans. Silage — hay or corn stalks that have been partially fermented — is also a common winter feed.

Traditionally, dairy cows were milked twice a day, in the morning and evening. Today, with the imperative throughout agriculture to produce as much as possible, it is common for farms to milk three times a day, and some large dairies milk four times a day, with the average U.S. cow producing nearly 23,000 pounds of milk annually.2 Milk production taxes the cow’s body, and pushing an animal to produce more shortens her life.

Dairy animal lifecycle

Like all mammals, cows produce milk after the birth of a baby. After a nine-month gestation and the birth of a calf, dairy cows are usually milked for about ten months, during which time they are impregnated again. They are then given a two-month rest before the birth of their next calf. A mature dairy cow produces a calf every 12 to 14 months.

Young cattle are called calves up to about five months. For their first two years, females are called heifers; once they give birth to a calf and begin milking, they are called cows. On average, farmers replace 25 to 40 percent of their cows every year, and many farms keep some or all female calves to raise as the next generation.

Cows are bred for specific purposes

While all cows produce milk, dairy cattle are breeds that have been bred for high milk production and quality. Holsteins and Jerseys are the most common dairy breeds. Beef cattle, like Angus and Hereford, are instead bred for rate of weight gain and yield. Beef cows produce milk for their calves, but do not produce enough for human consumption.

Definitions

Dairy farms use some specialized terms for their animals. Here’s what you need to know to not stand out around the barn.

| Heifer | A young female bovine who hasn’t yet given birth to a calf and is therefore not producing milk. |

| Cow | A female bovine who has given birth to at least one calf and has entered the milking herd. |

| Dry Cow | A cow who is between lactation cycles and not being milked. Typically this is for the last two months of a pregnancy. |

| Megadairy / Factory Farm | A dairy operation housing over 700 mature dairy cows in confinement. The technical term is Concentrated Animal Feeding Operation, or CAFO. |

| Grassfed / Pastured Dairy | A dairy farm whose cows get some or all of their nutritional needs from grazing on pasture (or eating hay in winter). |

The current dairy crisis

Since 2015, the price that farmers get for their milk has been well below what it costs them to produce; it costs them money to produce our nation’s milk supply. In the last year, farmers have been paid about $16 for 100 pounds of milk, while that amount costs them about $23 to produce.3 4 Four years of these prices mean farmers can’t pay for feed, seed, vet visits, equipment repairs — or even for heat, electricity or food for themselves and their families.5 Megadairies can absorb these losses, but family farmers cannot.

This price drop has caused dairy farms to close in record numbers. In the last year, for example, Wisconsin (the second largest dairy state), lost nearly 700 dairy farms, an almost 30 percent decline from the previous year.6 Trends are similar in other dairy states.

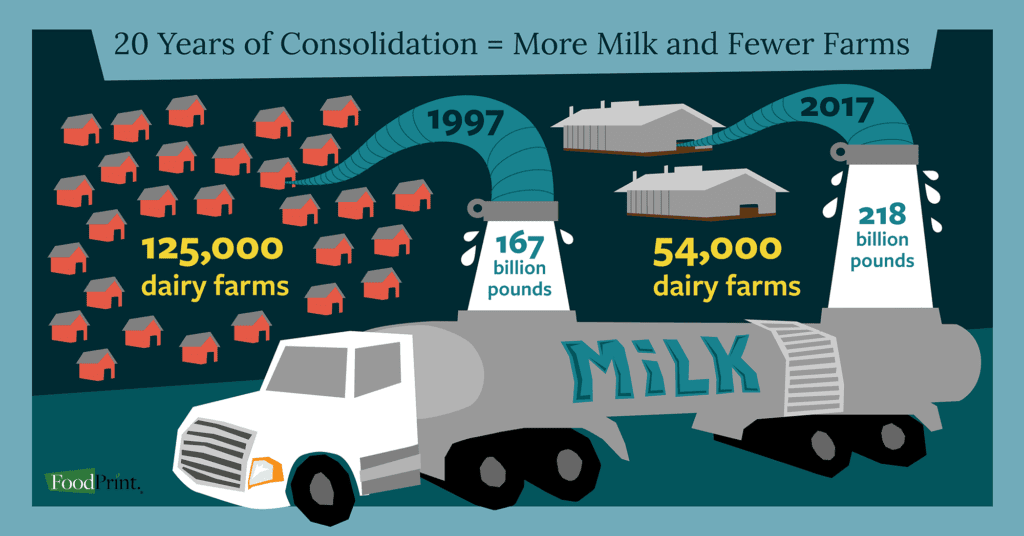

The situation today’s dairy farmers are facing is catastrophic, and comes on the heels of decades of dairy consolidation. In 1997, 125,000 U.S. dairy farms were milking 9 million cows.7 In 2017, the number of farms had dropped dramatically to 54,000, while the number of cows had grown to 9.4 million.8 9 In about the same period, annual U.S. milk production grew from 167 billion pounds to 218 billion pounds, meaning that much more milk is being produced by more cows but on many fewer farms.10 11 In fact, over half of all milk sales in 2017 were from operations with over 1,000 animals, with fully one-third of sales from dairies with over 2,500 cows.12

How milk pricing works

Dairy farmers sell their fluid milk to a processor, which bottles it or turns it into cheese, yogurt or another product. In economic terms, dairy farmers are called price “takers” rather than price “makers,” because the extreme perishability and constant milk production makes the farmer dependent on the processor. If the processor declines a farmer’s milk, the farmer has nowhere to put it because he only has limited storage and the cows will just keep producing milk the next day. This gives processors a great deal of power to pay whatever price they want; the farmer has to accept it or risk not having their milk picked up.

Dairy cooperatives

In an effort to gain more power over their own prices, dairy farmers established cooperatives, as far back as the 1800s.13 Pooling milk from many farms gave cooperatives the bargaining power to negotiate better prices for their farmer members and has continued to be a successful strategy for farmers for many years. However, dairy coops have evolved and grown; the largest today controls one-third of the US milk supply and is involved in all parts of the supply chain, including processing and distribution.14 Many farmer members of the largest dairy coops say the coops act more like corporations than organizations working on farmers’ behalf, pointing to expensive corporate offices, lack of transparency in dispersal of milk payments15 and, in the worst cases, outright corruption and collusion.16

Milk pricing is broken

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has also attempted to address farmer price issues and today sets regional base prices for milk.17 18 Unfortunately, that price today is not based on how much it costs a farmer to produce milk, including feed, fuel, equipment and other farm expenses. Instead it is based on market prices of milk products: butter, cheese, dry whey and powdered milk. Manufacturers of dairy products (which are usually the processors themselves) tell USDA how much they were paid for their butter and cheese every week; these numbers are then plugged into a complex formula that determines the price that processors must pay dairy farmers for their milk. Since it is not a system designed to cover farmers’ production costs, the base price is often far less than what farmers need to break even.

Further exacerbating the problem is a shrinking number of places that farmers can sell to. Historically, most regions had many dairy processors, so farmers — or their coops — could negotiate for a better price. Now, however, some regions only have one or two. In recent years, even the remaining processors have been consolidating, or they prefer to pick up milk from just a few large dairies instead of many smaller farmers. Some large grocery chains have now begun to produce their own milk, leading dairy processors that have supplied those stores to end contracts with their farmers. If the only processor in the region terminates farmers’ contracts, they are left without a place to sell their milk and few options besides selling off their cows.19

Get big or get out

With milk prices not adequately compensating dairy farmers for their work and costs, a fast-shrinking number of buyers, and cooperatives (which often seem to work against the interests of their farmer members), many smaller farmers have just two options: get big or get out. Large dairies can take advantage of economies of scale, as well as subsidies and tax incentives for expansion. Farmers, who cannot expand or who do not want to wait for milk prices to go back up, wait anyway until they can’t wait anymore and have to get out of the business. In the last year, surplus prices have dropped so low that even midsize dairies, which had expanded in recent decades (simply to remain viable), are also getting out.

Problems with megadairies

As long as there’s still enough milk to make all the Greek yogurt and ice cream we can eat, why does it matter if family farms close and all our dairy products come from huge industrial operations? After all, larger operations are more economically efficient in terms of equipment, land and other resources.

The answer is that big operations only look efficient if you don’t look at the externalized costs: all the costs created by the megadairies that are paid by someone else. If a manure storage lagoon leaks and pollutes the water table, as just one example, the operator generally doesn’t pay all the costs of cleanup. Instead, the town pays for a new water filtration system or individual families have to purchase bottled water. The megadairy can do business as usual, with other entities cleaning up its messes and picking up the tab. Megadairies treat cows inhumanely, pollute the air and water, and extract wealth from the local community instead of supporting the economy. In short, megadairies cause mega problems.

Animal welfare concerns with megadairies

Cows that are housed in megadairies have one purpose: to produce as much milk as possible. The near-constant production takes a toll on their bodies, and the conditions they live in can be stressful, leading to shortened lifespan.

The shortened lifespan of a megadairy cow

Dairy cows are pushed to produce so much milk that they are spent in just a few years. Dairy cattle can live to age 15 or 20, and in a humanely-managed herd, cows can effectively produce milk for 12 to 15 years.20 But in a megadairy, cows stay in the herd only until about age five, when their productivity begins to decline and they are sold to slaughter as beef. Dairy cows culled for low productivity or other reasons make up about 8 percent of U.S.-produced beef.21

Male dairy calves also have shortened lifespans. Not being able to produce milk, they are essentially extraneous to dairy production and are sold as meat — this is true not just at megadairies, but on most family-scale pasture-based farms, as well. Male dairy calves are sold either to be raised as full-grown beef cattle or as veal, to be slaughtered at 18 to 24 weeks of age.22

Physical manipulations of dairy cows

To adapt cows better to the close and stressful quarters of a megadairy, some operators perform painful mutilations on the animals, including removing part of their tails or their horns. Fortunately, these cruel practices are on the decline. Some animal welfare labels for dairy indicate that the animals did not undergo these procedures (see labels section below as well as our comprehensive Food Label Guide for Dairy).

Tail docking of dairy cows

Tail docking, the partial amputation of up to two-thirds of the tail, usually performed without anesthetic, has been controversial in the beef and dairy industries for years. The vast majority of research on the practice does not find benefits for improved hygiene or animal health; most dairies that dock cows’ tails cite worker comfort as the reason. However, many studies have shown that the practice causes pain, and increases animals’ long-term distress from flies.23 The practice is banned in several European countries and a few US states and is opposed by numerous scientists, veterinary groups and others.24 25 26 A 2005 survey found that tail docking was practiced by 82 percent of dairies,27 but this percentage has plummeted in recent years. By 2013, about half of all operations had cows with docked tails and only about a third of operations were still engaging in this practice.28

The dairy industry introduced a voluntary program calling for the discontinuation of all tail docking by the beginning of 2017. Dairies still engaging in this may be suspended from the program, which could make it harder for them to find a market for their milk.29

Dehorning of dairy cows

Removing the horns of dairy cattle reduces risk of injury to people and other cattle. Cattle less than eight weeks old can have their horn buds removed before they attach to the skull, called disbudding, while dehorning refers to the removal of horns after they have attached to the skull, but the terms are often used interchangeably. The practice causes pain and discomfort for the animal; as such, the American Veterinary Medical Association recommends procedures to reduce or eliminate these effects, including use of analgesics or anesthetics. Ninety-five percent of dairy operations practice disbudding/dehorning, but only 28 percent use pain medication. About a quarter of operations have avoided the issue altogether by breeding their animals with bulls that produce offspring without horns.30 31

How dairy cows are housed

Cow housing can vary a great deal between operations. The buzzword for housing in the dairy industry is “cow comfort,” as milk production slows when cows are hot, dry, hungry or otherwise uncomfortable. Even so, conditions can be dirty, overcrowded and hard on the animals’ bodies.

Free-stall barns, noted above, house cows in both medium and large operations in colder climates.32 Large operations in warm climates, such as the megadairies in California, Texas and New Mexico, often house cows on a dry lot, a large outdoor area with structures for shade. Both of these styles have separate areas for the animals to lie down, feed and be milked. Manure in free-stall barns is scraped or flushed out of the barn with water and stored in pits or lagoons (see details below); on dry lots, some of the manure turns into dust to be inhaled by the cows and the local community.33

Some of these operations give the animals sufficient space to move around and comfortable surfaces on which to walk and lie down, but many others do not. Flooring in indoor operations is generally concrete, which is hard, abrasive, and slippery, and can cause hoof damage.34 Another stressor in indoor dairies is stocking density: how many cows are in the facility.35 Too many cows can mean that those who are subordinate in the social order don’t get a place at the feed trough or enough time in a resting stall.36

Cows can spend 12 to 14 hours a day lying down, which is necessary for milk production and maintaining their general health. Cows actually place a higher priority on resting than they do on eating or socializing, indicating that it provides important biological functions.37 Resting places vary greatly among operations, from concrete covered with sand or sawdust to rubber mats. Like people, cows prefer lying down in soft and dry areas. Cows provided resting places that are too hard, wet or soiled spend less time lying down, which can make them stressed, decrease milk production and compromise their immune systems.38

Dairy cows should be eating grass

The digestive tracts of cattle have evolved to digest grass. The feed ration of most dairy cows that are housed indoors includes hay or silage (fermented plant matter, which they digest like grass),39 along with soybeans and corn, which they do not digest as well. A high percentage of grain in the diet can lead to acidosis, a condition of the digestive tract that can affect digestion and cause health problems from liver abscesses to lameness.40 Dairy cattle are also commonly fed byproducts from other industries, including brewers’ grains, cottonseed hulls, citrus pulp41 and blood meal,42 a dried blood slaughterhouse byproduct used as a source of protein. Some of these byproducts have negative consequences: for example, distillers’ grains, a by-product of ethanol production, increase ammonia levels in cattle waste — contributing to more odors43 and creating potential health problems for the cows and dairy workers.

Cattle kept in confinement, especially in overcrowded conditions, are more likely to be stressed than those grazing on pasture, and stress can make them prone to health problems.44 To prevent or treat infection, parasites and illness, dairy cattle are treated with a variety of drugs.45 46 Unlike hogs or beef cattle, dairy cows that are part of the milking herd are not given routine antibiotics, but these drugs are regularly given to heifers, which have not yet begun milking.47 Milk is routinely tested for residue of several common antibiotics and other drugs; when cows are given any of these drugs for a specific condition, their milk must be discarded until the drugs have passed out of their system. However, a 2015 investigation by the Food and Drug Administration found that a small percentage of milk tested positive for antibiotics that are not supposed to be used on dairy cows at all, which suggests that farmers are not necessarily following the rules.48

Megadairies and zoonotic diseases

The crowded conditions on megadairies provide an ideal environment for diseases to spread quickly between animals. This presents an obvious danger to the animals, but also public health risk: viruses and other pathogens can mutate to spread from livestock to humans. These illnesses, called zoonotic diseases, are a hazard of all kinds of industrial animal farming, and dairy is no exception.

In 2024, a strain of avian influenza, also called H5N1 or bird flu, was detected for the first time in cattle after circulating between wild birds and poultry flocks worldwide since 2022. As of April 2025, the strain has spread widely between U.S. dairy herds, appearing in at least 998 herds across 17 states.49 Contact with raw milk from infected cows, whether through shared equipment or mother-calf nursing, appears to be the primary way the infection is transmitted. So far, U.S. officials have mandated that milk-producing cattle be tested for the virus before they are shipped across state lines, but otherwise, federal officials have not enacted any biosecurity policies to prevent further spread. Dairy industry representatives have argued that bird flu presents low risk because most cattle show only mild symptoms, and that any mandatory control measures would be too burdensome to adopt.50

In addition to causing illness in cattle, bird flu from dairy cows has also infected multiple people. While most illnesses have been mild or asymptomatic, the ease with which the flu has spread has caused alarm among scientists, who warn it could further mutate to become more dangerous or spread easily among humans.51 Most cases have been workers on dairy and poultry farms, though California and Missouri have reported cases with no known contact with animals, signaling human-to-human transmission may already be happening.52

Raw milk, which is never safe for human consumption due to the high risk of contamination from illness-causing bacteria, is considered a high risk for bird flu transmission. FDA researchers found bird flu in 14 percent of milk samples they tested in May of 2024.53

Growth hormone use in dairy cows

In the late 1980s, scientists discovered they could produce recombinant bovine somatotropin (rBST, also known as recombinant bovine growth hormone, rBGH), a naturally occurring growth hormone, through genetic engineering. Injected into a dairy cow, the hormone increases milk production by 15 percent. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved its use in milk production in 1993. Milk produced from cows injected with rBST was the first genetically engineered food product to be approved by the U.S. government,54 though it is banned in Canada and the European Union.55

The use of the hormone was controversial from the beginning. Because the FDA had determined it was safe, no label was required on milk from cows treated with it, and consumers objected to the lack of transparency. A 1999 Canadian study found no definitive human health impacts from the hormone, but found a number of impacts on cows, including a 40 percent increase in infertility, a 55 percent increase in lameness, and a 25 percent higher rate of mastitis, a painful udder inflammation, which requires treatment with antibiotics.56

Despite this opposition, many economists predicted very high adoption rates of the hormone, but instead many farmers have found that it was not profitable,57 especially as consumer pressure made supermarkets and dairy processors no longer want to use treated milk.58 USDA reports that its use dropped from over 17 percent in 2007 to about 14 percent in 2014.59 60 Organic milk comes from cows not treated with rBGH.

Megadairies are bad for the environment

Cows on pasture can feed themselves and return their waste directly to the soil. Thousands of cows living in confinement, on the other hand, need their food and water delivered to them and their tremendous volume of waste must be removed. All these inputs and outputs take a serious toll on the environment.

Cows heat the planet

Perhaps the most dangerous emissions from dairy cows are the tremendous amount of greenhouse gasses they produce, through belching and flatulence. A dairy cow is estimated to annually produce more than 330 kg of methane, a greenhouse gas at least 25 times more potent than carbon dioxide.61 In California, the top dairy-producing state, dairy cows account for 45 percent of the state’s methane emissions and 38 percent of its nitrous oxide,62 another extremely potent greenhouse gas. Globally, the top five greenhouse gas-emitting meat and dairy companies together produce annual emissions greater than ExxonMobil, Shell or BP.63

Megadairies pollute the water

Megadairies also produce an incredible amount of manure. A 2,000-cow dairy generates nearly a quarter of a million pounds of manure daily, or almost 90 million pounds per year.64 Manure is high in nitrogen and phosphorus; these are important fertilizers in proper amounts but are toxic in excess. Nitrogen breaks down into nitrate, which causes algae blooms and dead zones in lakes and rivers. Nitrate is a human health hazard when it finds its way into groundwater,65 with the potential to cause serious illness in babies and pregnant women and an increased risk of colon, kidney and stomach cancers in other adults.66 Dairy waste can also contain pathogens such as E. coli or drug residues; wells in some counties with high concentrations of megadairies have tested positive for endocrine disrupting compounds.67

At megadairies, waste is generally stored in large open ponds, called lagoons, and sprayed onto cropland as fertilizer or injected into the ground. The lagoons release methane and are prone to leaks, releasing toxic liquid manure into ground or surface waters. In just one dramatic example from 2015, nearly 200,000 gallons of manure spilled from a storage tank in Oregon, flowing across private property, into a river and a bay. State officials had to close the bay to fishing for a week.68

Leaks are not the only problem. The manure from that 2,000-cow dairy contains as much nitrogen as sewage from a community of 50,000 to 100,000 people.69 That’s so much fertilizer that the standard practices to dispose of it are simply inadequate. It is not uncommon for operators to spray it onto fields at rates higher than the soil can absorb or under conditions that aren’t ideal, causing it to run off into nearby waterways or seep into groundwater. In some regions, land values have increased due to demand by dairy operators for a place to dispose of their excess manure.70

Dairy production is thirsty

Megadairies also need a lot of water to produce milk. Milk is about 87 percent water,71 so cows have to drink several gallons of water daily when they’re milking. Flushing all the manure and keeping the milking equipment clean takes even more: estimates range from 30 to 50 gallons of water per cow per day.72 This is especially troubling considering the expansion of megadairies in dry states like New Mexico, Texas and California.

Even Wisconsin, a state with abundant water resources, is struggling with how much water dairies are drawing from aquifers. High-capacity wells that draw over 100,000 gallons per day are proliferating to feed large dairies and intensive crop production. As a result, lakes and rivers are drying up, impacting property values73 and tourism in the state.74

Megadairies pollute the air

Huge ponds of manure have an obvious downside for the neighbors: they stink. The odors from a megadairy can dramatically impact the health and quality of life of surrounding areas, making it difficult for local residents to go outdoors.75 Ammonia and hydrogen sulfide, two of the major pollutants from dairy manure, irritate the respiratory system and at high doses can even cause death.76 Particulates (tiny dust particles from dried manure), dust and feed have similar impacts. Cities in California’s San Joaquin Valley, near the heart of the state’s dairy country, have some of the highest rates of particulate pollution in the nation.77 Tens of thousands of dairy cows are chief among the contributing factors.78

Some states have laws and regulations regarding odor and emissions from CAFOs,79 but at the federal level, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) does not require farm operations to report air emissions. In 2018, the EPA exempted farms from the two environmental laws that require reporting releases of hazardous substances.80 The exemption was ostensibly to ease the regulatory burden for family farms, which have much lower emissions, but in practice, it shields industrial-scale dairies from any transparency about their air pollution and its burden on surrounding communities.

Animal waste and methane digesters

Some constituencies, from the dairy industry to some environmentalists, promote anaerobic manure digesters as an environmentally sustainable way to manage the huge amounts of manure generated by factory farms. Unlike an open lagoon, a digester is a closed environment, using microbes, heat, water and agitation to process the waste. The methane is captured for energy, and the other manure outputs are cleaned of phosphorus and pollutants, making them safer to spread as fertilizer. The federal government has invested millions in digester research81 and some states offer significant incentives for their construction.82 83

Sounds good, but digesters do not make megadairies “green.” Despite all the public investment in the technology, a new digester costs anywhere from half a million dollars to $2 million, making them not economical to build or operate without significant subsidies.84 85 Instead of coming up with alternate solutions for how to store and manage animal waste, a “digester-first” model of managing manure assumes that huge manure lagoons are a necessary part of dairy production. Digesters need a steady high volume of waste to run efficiently, so the model of one megadairy supporting one digester further entrenches the large-scale confinement model of agriculture.86 The expenditure of public research and subsidy dollars in this technology also comes at the expense of similar investment in composting systems or pasture management.

Big dairy is a bad neighbor

The growth of megadairies has significant impacts on local communities, both in the regions where family dairy farms are closing and those where thousands of cows are being moved in.

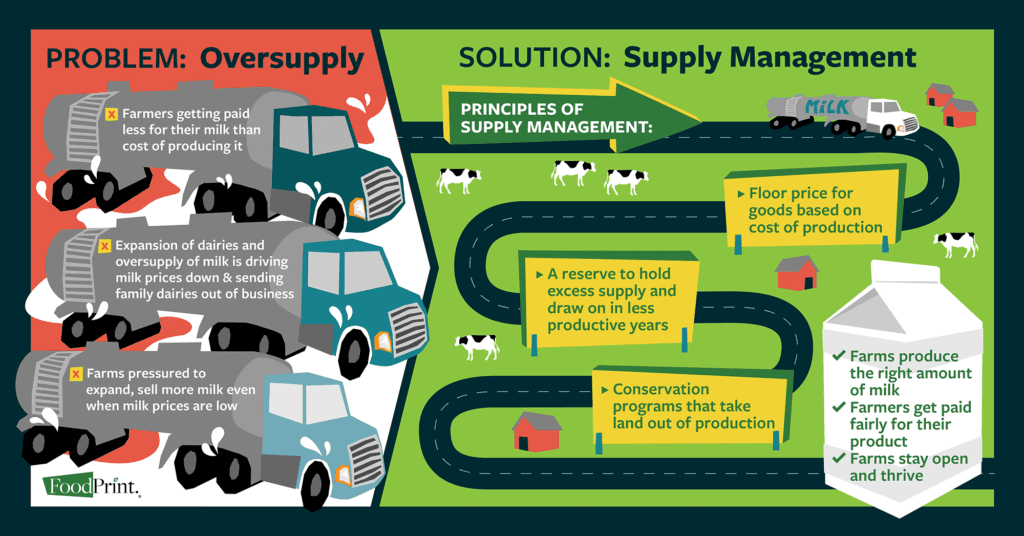

Big dairy ruins local economies

The expansion of megadairies and resulting oversupply of milk is a major factor driving milk prices down87 and sending family dairies out of business. Squeezed by low prices, farmers are foregoing major purchases88 and cutting household expenses. Farmers still trying to hang on are sometimes unable to pay their electric bill or buy groceries. One dairy cooperative sent out information about suicide hotlines with the milk checks and calls to farmer support hotlines have increased.89

In addition to the grave psychological toll this takes on the family, the lost income has a ripple effect throughout the local economy: as farmers cut back, the supermarket, clothing store, coffee shop and other businesses earn less.

Across all livestock sectors, small and mid-size farms spend more at local businesses than factory farms do.90 Large shipments of feed ingredients and medications lend themselves to volume discounts from faraway dealers, and a megadairy is likely to have a veterinarian, as well as mechanics and other specialists on staff, rather than using the services of the community. Numerous studies in the last 50 years show that factory farms result in lower relative incomes; greater income inequality and poverty; a less active Main Street; a lost multiplier effect from interrelated business activity and fewer stores.91

The local economy loses out when family dairy farms close. And when a megadairy moves in, often receiving considerable tax breaks, its neighbors have to pay the real costs of the externalities that it offloads. In some dairy-intensive regions in California,92 Oregon93 and Wisconsin,94 the water table has become so polluted with animal waste that residents must purchase water to drink, cook and bathe with. In Wisconsin, property values of homes near megadairies have dropped by nearly 15 percent.95 Megadairies, often owned by companies headquartered in another state, are just as environmentally taxing an industry as coal or natural gas, polluting the land, extracting water and sending earnings out of the community.96

Worker welfare concerns in dairy industry

Small farms generally rely on the family or sometimes a hired hand to milk cows and run the farm. Large dairies milking thousands of cows three times a day need considerably more labor, and megadairies will tout job creation as a benefit to the local economy. The reality, as on most farms, is that the majority of dairy workers are immigrants,97 not long-time community residents. Since the dairy industry is year-round, dairy operations are not eligible to hire legal workers through the seasonal H-2A guest worker program, so they turn to undocumented workers. In one survey of New York State dairy workers, 93 percent were undocumented.98 Fearing deportation, these workers are less likely to speak up or complain about poor treatment or conditions.

In many dairies, conditions are appalling. The work is physically difficult, smelly, dangerous and has long hours for low pay. Twelve-hour days are the norm, with only rare days off and no overtime pay. While dairies pay an average of $11 to $12 per hour, workers are usually hired only if they have a social security number (usually fake), and so they take home more like $9 per hour after taxes.99 (And, since they are not officially paying into the system, they will never reap the benefits of those taxes.) Workers are often provided housing, but it is often substandard and overcrowded, and many workers feel isolated in rural communities.100 Working with large animals, heavy machinery and slippery surfaces, injuries and infections101 are common and deaths sometimes occur.102 Over the course of five years in the 1990s, there were 12 documented worker deaths in manure lagoons.103

Because they work closely with animals and handle raw milk, dairy workers are far more likely than other people to contract zoonotic diseases like bird flu. During the ongoing 2024 outbreak, dozens of dairy workers across the U.S. have contracted bird flu, with the C.D.C. finding in one study that at least 7 percent of sampled workers had bird flu antibodies that indicated infection.104 While all the affected workers have shown mild symptoms, public health experts warn that these exposures significantly increase the risk of mutations that could make bird flu more transmissible in humans. The CDC recommends workers in contact with infected animals be provided with personal protective equipment (PPE), including gloves, goggles and a respirator.105 But because these protections have not been mandated by state and federal health departments, most workers remain unprotected, putting them and their family members — especially those with underlying conditions that might make them more vulnerable to the virus — at risk.

How state policy supports megadairies

Megadairies have been able to grow and operate recklessly thanks to lax state policy. In many states, lawmakers have passed laws and enacted regulations that make it easier for megadairies to operate, even in the face of local opposition. Promising jobs and economic development, which rarely materialize, operators often expect — and receive — tax breaks and other public subsidies to build their operations.

Here are a few examples:

- Operators are not responsible for everyday leaks or seepage; this reduces costs for a megadairy. In Wisconsin, state regulations allow manure lagoons to leak up to 500 gallons per acre per day.106 Some lagoons are as large as four acres, allowing them to legally leak 2,000 gallons per day onto surrounding land and waterways with no responsibility for cleanup.

- Many states offer tax exemptions that benefit factory farms over small or pasture-based farms. Small farms can take advantage of some of these exemptions, such as for farm equipment, land or livestock, but they are of greater benefit to large operations: the tax savings on 2,000 cows is greater than on 50. Across the country, tax exemptions are common on sales of supplies like livestock feed and bedding, pesticides and animal medications, and on construction and improvement of manure storage facilities and animal housing.107 108 109 110 These tax breaks are not designed for pasture-based farms, which grow most of their own feed, use fewer medications, and need housing and manure storage for their animals only in inclement weather — but they can mean huge savings for megadairies.

- In Iowa, counties are effectively barred from contesting a new factory farm (or CAFO — concentrated animal feeding operation), due to a 1995 law that also opened the door to corporate ownership of livestock. The law protects all farms — even factory farms — from nuisance lawsuits and prohibits counties from adopting any zoning, public health or land use provisions that might restrict construction of a CAFO. While many farm states have retained their local control over factory farm siting, a few states like North Carolina have similar restrictions.111

Fighting megadairies with the law

Since megadairies are supported by the law, communities across the country have also turned to the law to fight them. For example, in 2012, a U.S. Environmental Protection Agency study showed that wells in a part of Washington State with several megadairies had extremely elevated nitrate levels, posing serious danger to the residents who rely on the wells for drinking water. When the state agencies responsible for regulating the dairies took no action, community groups sued the dairies in 2015 for violation of water protection laws.112 In a groundbreaking decision, the court ruled that the dairies were responsible for the water pollution and in a subsequent settlement, the dairies agreed to implement changes in their operations.113 Two years later, Washington State implemented new water protections for dairies with more than 200 cows.114

In eastern Oregon, the debacle of one failed megadairy prompted proposal of broader legislation. Lost Valley, a 30,000-cow megadairy, was plagued with problems from the start; it opened with its waste management infrastructure only partially built and water rights secured only through a legal loophole. The operation racked up the most fines the state had ever issued to a dairy before declaring bankruptcy 18 months later, leaving 30 million gallons of manure awaiting cleanup.115 Area residents, tired of the slow pace of enforcement by state agencies and all too aware of the threat that megadairies pose to local economic and environmental health, worked with state lawmakers to introduce legislation calling for a temporary moratorium on dairies with more than 2,500 cows.116

Similar measures have been proposed or introduced in states including Wisconsin, Indiana and Iowa, addressing not only megadairies but other new or expanded large livestock operations.117 The meat and dairy industries, which often promote the interests of mega-operations rather than the interests of independent farmers, are politically powerful, especially in so-called “farm states.”118 119 As a result, none of these moratorium laws has passed so far, but as more and more people from farm states to suburbs to big cities want a food system that’s good for themselves, farmers, workers, animals, local communities, the environment and public health, momentum will continue to build for these measures.

The promise of grassfed dairy

There is an alternative to keeping thousands of cows confined in a barn or a dusty dry lot, wreaking havoc on the community: small-scale family farmers can instead raise cows on lush pastures. Grassfed cows are healthier, and these farms are much better for the animals, the environment, the farmers and the community.

Better animal welfare

Overall, cows grazing on pasture are healthier, including getting fewer hoof and udder infections, common in cows raised in confinement. Their diet is more varied, consisting of the grasses they evolved to digest (sometimes supplemented with additional minerals as the farmer deems necessary), and can move freely and express all of their natural behaviors. Common dairy breeds like Holsteins and Jerseys do fine on grass, but some farmers decide to transition their herds to breeds even better adapted to an all-grass diet,120 bringing some much-needed genetic diversity to the dairy industry.

It should be noted, however, that cow housing is not necessarily bucolic on small farms, even those where cows spend most of their time on pasture. Many small farms use old barns, with stanchions or tie-stalls that tether the animals loosely by the neck, limiting their movement.121 In cold climates, cows may spend most of the winter in stanchions before being let out to pasture when temperatures rise.

Better for the environment

Pastured cows still produce methane as a natural part of their digestive process, but that does not mean that cattle are inherently bad for the climate. Grasslands coevolved over millennia with grazing animals like buffalo and elk, and dairy cattle, in appropriate numbers, have the same positive impact on the land that these animals do. Well-managed grasslands have the potential to sequester literal tons of carbon dioxide and grazing plays a vital role in keeping those ecosystems healthy.122

The size of a grazing herd is kept in check by the capacity of the land, eliminating many of the waste management and other problems that arise from thousands of animals. Instead, cows grazing on pasture deposit most of their waste directly on the land, where it breaks down naturally and fertilizes the soil. Pasturing systems called intensive rotational grazing keep the animals on small sections of pasture for short periods and then move them to the next section, allowing the just-grazed one to rest. The intense grazing, trodding of hooves and fertilization coupled with longer regrowth periods builds healthy soil structure and microorganisms and stimulates deeper roots and more lush pasture growth.123 Deep plant roots control erosion and make the soil able to retain more water, mitigating drought and reducing flooding.

Better for your health

Cows that get their nutrition from the diverse range of grasses they have evolved to eat make milk that is healthier to drink. Milk contains some of the essential fatty acids that the human body must get from food, including omega-3, which contributes to heart health and reduces inflammation, and conjugated linoleic acid, which has cancer-fighting properties.124 125 Grassfed milk has more of these good fats than organic milk — and nearly twice the levels found in conventional milk. 126 Levels of carotenoids, which are beneficial for cardiovascular and eye health, are also higher in milk from pastured cows. 127

Better for the community

Small family-run dairy farms are better for the local economy and community than megadairies, which make more purchases remotely and send profits out of state. Dairy farmers spend their money locally — not just on farm equipment, but in the grocery store and coffee shop too. A 2014 study estimated that Vermont’s dairy industry, where most dairy farms are still small (only 2 percent of the state’s dairies have more than 700 cows), brings $3 million in circulating cash to the state every day.128 And while many dairy cooperatives have consolidated and have distant corporate headquarters, some family dairy farmers still belong to small local cooperatives that return profits to farmers and support the community.129

Family dairy farmers collectively steward millions of acres of open space, valued for recreation, tourism, natural beauty and ecosystem services like water filtration and wildlife habitat. In the six New England states, for example, the 2,000 remaining dairy farms tend 1.2 million acres of farmland and produce almost all of the milk consumed in New England.130 Just in Vermont, 900,000 acres — 15 percent of the state — is dairy farms and fields. The classic New England landscape of rolling fields and open pastures attracts new residents and tourism dollars — and is tended largely by dairy farmers. The same is true in other dairy regions.

Better for workers

Pasture-based dairy farms do not rely on full-time, onsite labor like megadairies do. With smaller herds of cows out to pasture, harvesting their own feed and leaving their waste to build soil, there is less need for human labor.

For dairies that are not grass-based and do still rely on labor, there are alternatives to the worker exploitation common at megadairies. The Milk with Dignity Program, developed by Vermont-based advocacy group Migrant Justice, requires certain standards of worker rights at participating farms, and includes rights education and a third party monitor to ensure compliance. Ben & Jerry’s is the first company to join Milk with Dignity, guaranteeing that all the dairy farms in its supply chain are adhering to the programs’ standards.131

Better for farmers — sometimes

For farmers, transitioning to a grazing system can mean much lower costs — via reducing or eliminating feed, machinery and labor — and less work.132 However, cows exclusively eating grass produce less milk,133 so it is not a perfect trade-off. If farmers have to sell a lower volume of grassfed milk into the regular commodity market, they will lose money; but with rising consumer interest in and third-party labels for grassfed dairy products,134 there may be nearby processers that will offer a premium for grassfed. In that case, the transition can be a lifesaver for struggling farms.

Farmers who can’t make ends meet and don’t have a nearby processer buying grassfed milk have another option: they can market their own. Some dairy farms decide to bottle their own milk or make cheese or yogurt. By opting out of the commodity milk system, they can set their own price and capture more of the consumer’s dollar.

Some farmers have great success going this route, but it’s not for everyone. Like any value-added farm enterprise, on-farm processing requires more labor, specialized skills and often, less time farming, as marketing, administration and other demands take over. For dairy farmers, it’s expensive to process their own: equipment for a small-batch cheese operation from 50 cows can start at $75,000, milk bottling at nearly $100,000. Capital costs for a small bottling plant for just 175 cows are close to $1 million.135

Milk: Not just from cows

Of course, not all milk comes from cows — or even from animals.

Sheep and goat cheese are increasingly popular in the U.S. The goat milk market is steadily growing too, expected to reach revenues of $15 billion worldwide by 2024.136 Dairy goat herds expanded more than 60 percent in the latest USDA Census of Agriculture, much faster than any other livestock. Unfortunately, trends in dairy goat farming already mirror those in other sectors: the number of animals is increasing while the number of herds is decreasing, which indicates consolidation in the industry.137

While Americans mostly stick to cow milk, people around the world drink milk from any number of animals. In Tibet, where yaks thrive in the cold mountain environment, yak milk and butter are dietary staples. Camel milk is drunk in the Middle East, and many Americans are familiar with Italian mozzarella made with milk of water buffaloes.

And then there are non-dairy “milks.” Soy milk has been consumed across Asia for centuries, and has been popular in the U.S. for a decade or more. Today, the market for plant-based milk substitutes is booming, growing 61 percent between 2012 and 2017, and includes almond, oat, flax, coconut and hemp, to name a few.138 Some in the dairy industry object to the rise of these alternatives, which they say are cutting into the market for cow’s milk. The issue has become so contentious — and the dairy trade associations and cooperatives have become so politically powerful — that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has gotten involved, and is expected to release guidance this year on what products can and can’t be marketed as milk.139

Building a better dairy system

Moving towards a system where cows are raised on pasture by family farmers making a living wage will require all of us to make all the efforts we can, as consumers at the grocery store and as engaged citizens making our voices heard. We need to make the best choice in the supermarket whenever we can, to get the better option (if the best is not available) — and we need to support efforts to build a healthier system for cows, farmers and consumers.

Consumer choices: Finding milk you can trust

If you’re sticking to cow’s milk and you want it grassfed, you’ll be glad to know that the supply is growing fast. That said, it’s not available everywhere and it can be hard to know which labels to look for to ensure you’re getting what you want.

Consumers who are used to inexpensive dairy may balk at the price difference between conventionally-produced and organic or grassfed. If you are financially able to do so, consider adjusting your thinking about this price and spending that little bit more as an investment in developing a healthier food system for all.

Defining grassfed

As the grassfed market grows, there is little regulation of the term itself. Some farmers graze their animals on pasture but supplement their cows’ diets with grain, usually to boost milk production. Milk from these cows can still be called grassfed. Some pasture is better than none, and that’s a good choice if it’s available.

For milk that comes from cows eating nothing but grass (including hay in the winter), look for labels that say “100% grassfed,” Organic Valley’s Grassmilk or the Certified Grass-Fed Organic seal and certification, launched by Organic Valley and Maple Hill in early 2019.

What about organic dairy?

Unlike most other labels, USDA Organic is regulated by the federal government. USDA Organic dairy rules state that cows cannot be given growth hormones or antibiotics; any use of antibiotics, even to treat illness, requires permanent removal of the animal from the herd. All feed must be certified organic, must not contain animal by-products, and the animals must not be continuously confined.140 After multiple investigations in the late 2000s revealed that some large dairies were not pasturing their animals, contrary to the intent of the organic standards,141 a “pasture rule” was added, mandating that all organic dairy animals must graze on pasture for a minimum of 120 days per year and must get at least 30 percent of their intake from grazing pasture during the grazing season.142

Some organic dairies are failing to meet standards

However, recent investigations have found that some large organic dairies are not meeting these grazing standards.143 While farm size is not a definite indicator of dairy quality, moving many cows from pasture to milking parlor takes time, and at a certain point it is logistically impossible that operations milking thousands of cows three or four times a day could make the necessary moves and still give their animals sufficient grazing time.144

Additionally, organic dairies that feed grain as well as pasture must use organic grain. The U.S. imports much of our organic grain because we do not produce enough to meet the demand for organic feed, but numerous shipments of foreign corn, soybeans and other grains labeled “organic” have been found to be fraudulent in recent years.145

Despite these questionable practices, many megadairies retain their organic certification. This is due to USDA’s unusual enforcement mechanism: USDA does not certify or inspect organic farms itself. Instead, each farm hires a third-party certifying agency to judge whether it meets organic standards. Most inspections are announced in advance, and punishments for violations are minimal. From 2007 to 2010, there were at least three cases of significant violations found on organic megadairies, but USDA issued no fines and all continue to operate today.146

“Industrial organic” hurts small organic farmers who are following all the rules. Certified organic megadairies are flooding the organic market with milk they have produced much more cheaply and with lower standards than small farms do. Organic milk prices for farmers have fallen and some organic and grassfed processors have dropped farmers due to oversupply.147 For organic dairy to have a strong future, USDA and the inspection agencies must enforce the organic rules, including on the largest players in the industry.

What does this label mean?

Labels can be complicated. There are great labels that certify environmental and animal welfare standards, but they are not always widely available. As for finding dairy products produced by family farmers and workers both making a living wage — there is no label at all for those considerations, though you can be confident that certified grassfed milk comes from small and medium-sized family farms.

Where available, look for these labels:

- Certified Grassfed by A Greener World

- American Grassfed Association Grassfed Dairy

- Certified Grass-Fed Organic Livestock Program, by Organic Valley and Maple Hill

The Cornucopia Institute, an organic watchdog group, also maintains a comprehensive Organic Dairy Scorecard, rating many large and small organic brands on percentage grass fed, number of daily milkings, care of pasture and much more.

The big picture: Supporting small dairy farmers through policy change

If your grocery store carries certified grassfed dairy products, or a farmer sells fresh milk or cheese at your farmers’ market — buy it! However, supporting small and medium-sized dairy farmers can be challenging for the consumer, because dairy is such a complicated and opaque industry.

While some small farmers are able to switch to grassfed production or value-added production, many more are not, due to expense or lack of market. When milk prices are so low, these are the farmers most at risk of closing — and unfortunately, they are the ones who are hardest for consumers to support. These farmers, who might milk anywhere from 40 cows to 400, know their cows well and likely give them some time on pasture, preserve open space by growing their own feed, spend their money locally and more. They may not all meet the grassfed ideal, but they are a far cry from a megadairy.

But because there are so few processors left, these small and mid-size farms don’t have much choice about where their milk goes. Usually their nearest processor picks it up, to bottle it for the grocery store or turn it into yogurt or cheese. The milk of the 200-cow dairy and the 2,000-cow dairy all get mixed together, even if the smaller farm uses better practices and its milk is of a higher quality. Not only that, both farms get paid the same base price per hundred pounds of milk. When that price is well below the cost of production, the larger dairy can better absorb the loss. The smaller farm is more likely to go out of business — perhaps selling its cows to the larger facility and perpetuating the seemingly endless consolidation of the industry.

A different dairy system is possible: The need for supply management

Until we address the fundamental problem of low milk prices, the dairy industry will continue to consolidate, eventually leaving nearly all of us to get our milk from megadairies. And until we can guarantee dairy farmers a fair price based on their costs of production, we should not expect them to take on the costs of individually shifting to more sustainable practices.

The most significant and essential change we need to see in the dairy industry must come from federal policy. The U.S. used to have a policy that guaranteed farmers a fair price and kept them from rampant overproduction and its consequences. The policy, known as supply management, works well in Canada, where dairy farmers have secure livelihoods and can pass on their farms to the next generation.148

The main principles of supply management are a floor price for goods based on the cost of production, a reserve to hold excess supply and draw on in less productive years, and conservation programs that take farm land out of production. For the dairy industry, these measures would control how much milk is produced nationwide, stabilize prices for farmers, and ensure that consumer demand is met despite seasonal fluctuation.149

If a farmer knows he is getting a price that will cover his costs, he can pay his workers a fair wage and better manage his land and cows. Currently, a struggling farm is pressured to expand, to sell more milk to make more money, even when milk prices are so low. Under a supply management system, a farm would not have to expand — with all of the environmental and economic risks that come with getting bigger — because it would be generating a living wage as is.

Instead, the 2018 farm bill, passed during the most serious dairy crisis in 30 years, maintained the status quo for dairy, offering only a minimal insurance program that will not keep struggling farms in business. It will be up to consumers to advocate for justice for dairy farmers.

Conclusion

Dairy farms can have huge benefits for a community — or they can be a nightmare. The dairy industry is one of the most complex and opaque parts of our food system, and so it is especially difficult for consumers to know which kind of dairy their milk or cheese comes from.

The good news is that in recent years, the public’s desire to learn more about where our food comes from has made a difference even in in dairy. Growth hormones have gone out of favor due to consumer demand, and grassfed milk has become popular. At the same time, family dairy farmers are going out of business at an alarming rate and megadairies are expanding.

But the dairy price crisis is causing enough pain in rural America and grabbing enough headlines that real policy solutions like supply management are under discussion. To maintain integrity of the organic label, USDA also must be pushed to enforce its standards. Consumers, environmentalists and farmer advocates all must raise our voices in support of these changes and more. Together, we can shift the dairy industry to be fairer and more humane for all.

What you can do

- Support Grassfed production by purchasing milk that is certified grassfed. Learn more about Dairy Labels and what to look for in our Food Label Guide.

- Advocate for justice for dairy farmers. Learn more about policies that affect them by following organizations like Farm Aid, National Family Farm Coalition, and the Dairy Together Coalition led by the Wisconsin Farmers Union.

- Advocate for strong organic dairy standards. Learn more about these policies by following The Cornucopia Institute, The Organic Consumers Association and the Northeast Organic Farming Association (NOFA).

Researched and written by:

Hide References

- USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. “Dairy 2014: Dairy Cattle Management Practices in the United States, 2014. Report 1.” USDA, February 2016. Retrieved April 17, 2019, from https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/nahms/dairy/downloads/dairy14/Dairy14_dr_PartI.pdf

- National Agricultural Statistics Service. “Milk Production, Disposition, and Income. 2017 Summary.” USDA, April 2018. Retrieved April 17, 2019, from https://downloads.usda.library.cornell.edu/usda-esmis/files/4b29b5974/4j03d209m/qr46r324g/MilkProdDi-04-26-2018.pdf

- YCharts. “US Milk Farm Price Received.” (Translated from cwt to gallon.) YCharts, April 3, 2019. Retrieved April 17, 2019, from https://ycharts.com/indicators/milk_price

- USDA Economic Research Service. “Milk cost of production by State.” United States Department of Agriculture, October 2, 2018. Retrieved May 29, 2019, from https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/milk-cost-of-production-estimates/ on April 22, 2019.

- Chrisman, Siena. “Is the second farm crisis upon us?” Civil Eats. September 10, 2018. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://civileats.com/2018/09/10/is-the-second-farm-crisis-upon-us/

- USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service. “Number of Monthly Milk Cow Herds, Wisconsin, 2004 to Current, 1/.” United States Department of Agriculture, (n.d.). Retrieved February 21, 2019, from https://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/Wisconsin/Publications/Dairy/Historical_Data_Series/brt2004.pdf

- USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service. “2017 Census of Agriculture: Milk Cow Herd by Inventory and Size.” United States Department of Agriculture, 2019. Retrieved April 22, 2019, from https://www.nass.usda.gov/Quick_Stats/CDQT/chapter/1/table/17/state/US

- Ibid.

- USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service. “Milk Production.” United States Department of Agriculture, March 12, 2019. Retrieved April 22, 2019, from https://release.nass.usda.gov/reports/mkpr0219.pdf

- Blayney, Don. “The Changing Landscape of U.S. Milk Production.” United States Department of Agriculture Statistical Bulletin Number 978, June 2002. Retrieved April 22, 2019, from https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/47162/17864_sb978_1_.pdf?v=41056

- USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service. “Milk Production.” United States Department of Agriculture, March 12, 2019. Retrieved April 22, 2019, from https://release.nass.usda.gov/reports/mkpr0219.pdf

- USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service. “2017 Census of Agriculture: Milk Cow Herd by Inventory and Size.” United States Department of Agriculture, 2019. Retrieved April 22, 2019, from https://www.nass.usda.gov/Quick_Stats/CDQT/chapter/1/table/17/state/US

- Pitman, Lynn. “History Of Cooperatives In The United States: An Overview.” University of Wisconsin-Madison Center for Cooperatives, revised December 2018. Retrieved April 17, 2019, from https://resources.uwcc.wisc.edu/History_of_Cooperatives.pdf

- Douglas, Leah. “How Rural America Got Milked.” The New Food Economy, January 18, 2018. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://newfoodeconomy.org/how-rural-america-got-milked/

- Nargi, Lela. “What’s Behind the Crippling Dairy Crisis? Family Farmers Speak Out.” Civil Eats, November 5, 2018. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://civileats.com/2018/11/05/whats-behind-the-crippling-dairy-crisis-family-farmers-speak-out/

- Douglas, Leah. “How Rural America Got Milked.” The New Food Economy, January 18, 2018. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://newfoodeconomy.org/how-rural-america-got-milked/

- Farm and Dairy Staff. “What is the Federal Milk Marketing Order?” Farm and Dairy, February 7, 2018. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://www.farmanddairy.com/news/what-is-the-federal-milk-marketing-order/469448.html

- USDA Agricultural Marketing Service. “Federal Milk Marketing Orders.” United States Department of Agriculture, (n.d.). Retrieved May 29, 2019, from https://www.ams.usda.gov/rules-regulations/moa/dairy

- Chrisman, Siena. “Is the Second Farm Crisis Upon Us?” Civil Eats, September 10, 2018. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://civileats.com/2018/09/10/is-the-second-farm-crisis-upon-us/

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. “Ag 101: Dairy production: Lifecycle production phases.” EPA, date uncertain. Retrieved May 29, 2019, from https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-07/documents/ag_101_agriculture_us_epa_0.pdf

- Boetel, Brenda. “In The Cattle Markets: Dairy Cattle Impact on Beef Supplies.” Drovers, October 31, 2017. Retrieved May 29, 2019, from https://www.drovers.com/article/cattle-markets-dairy-cattle-impact-beef-supplies

- Humane Society Veterinary Medical Association. “Facts on Veal Calves.” HSVMA, 2018. Retrieved from https://www.hsvma.org/facts_veal_calves

- The Humane Society of the United States. “An HSUS Report: Welfare Issues with Tail Docking of Cows in the Dairy Industry.” HSUS, October 2012. Retrieved May 29, 2019, from https://www.humanesociety.org/sites/default/files/docs/hsus-report-tail-docking-dairy-cows.pdf

- Ibid.

- Botheras, Naomi. “Tail Docking of Dairy Cattle: Is it beneficial or a welfare issue?” Ohio Dairy Industry Resources Center, Ohio State University Extension, Volume 8, Issue 3, (n.d.). Retrieved May 29, 2019, from https://dairy.osu.edu/newsletter/buckeye-dairy-news/volume-8-issue-3/tail-docking-dairy-cattle-it-beneficial-or-welfare

- American Veterinary Medical Association. “Welfare Implications of Tail Docking Cattle: Literature Review.” AVMA, August 29, 2014. Retrieved May 29, 2019, from https://www.avma.org/KB/Resources/LiteratureReviews/Pages/Welfare-Implications-of-Tail-Docking-of-Cattle.aspx

- Fulwider, WK et al. “Survey of Dairy Management Practices on One Hundred Thirteen North Central and Northeastern United States Dairies.” Journal of Dairy Science 91, Issue 4: 1686-1692, April 2008. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022030208712979

- USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. “Dairy 2014: Health and Management Practices on U.S. Dairy Operations, 2014. Report 3.” United States Department of Agriculture, February 2018. Retrieved May 29, 2019, from https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/nahms/dairy/downloads/dairy14/Dairy14_dr_PartIII.pdf

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Hanson, Maureen. “Polled Dairy Genetics: Facts and Fallacies.” Dairy Herd Management, February 9, 2019. Retrieved May 29, 2019, from https://www.dairyherd.com/article/polled-dairy-genetics-facts-and-fallacies

- USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. “Dairy 2014: Health and Management Practices on U.S. Dairy Operations, 2014. Report 3.” USDA, February 2018. Retrieved May 29, 2019, from https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/nahms/dairy/downloads/dairy14/Dairy14_dr_PartIII.pdf

- Flaherty, Ryan and Cativiela, JP. “California Dairy 101: Overview of Dairy Farming and Manure Methane Reduction Opportunities.” Dairy and Livestock Working Group, August 21, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://arb.ca.gov/cc/dairy/documents/08-21-17/dsg1-dairy-101-presentation.pdf

- Gooch, C. “Flooring Considerations for Dairy Cows.” eXtension, September 28, 2012. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://articles.extension.org/pages/65155/flooring-considerations-for-dairy-cows

- Dairy Herd Management. “Pay Attention: Dairy Cow Stocking Density.” Dairy Herd Management, April 19, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://www.dairyherd.com/article/pay-attention-dairy-cow-stocking-density

- Buza, Marianne. “Feed bunk stocking density can impact dairy cow productivity.” Michigan State University, MSU Extension, January 5, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/feed_bunk_stocking_density_can_impact_dairy_cow_productivity

- Krawczel, Peter. “The Importance of Lying Behavior in the Well-Being and Productivity of Cows.” University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture, (n.d.). Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://extension.tennessee.edu/publications/Documents/W386.pdf

- Ibid.

- USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. “Dairy 2014: Dairy Cattle Management Practices in the United States, 2014. Report 1.” USDA, February 2016. Retrieved April 17, 2019, from https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/nahms/dairy/downloads/dairy14/Dairy14_dr_PartI.pdf

- Beauchemin, Karen A. and Penner, Greg. “New Developments in Understanding Ruminal Acidosis in Dairy Cows.” eXtension, February 3, 2014. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://articles.extension.org/pages/26022/new-developments-in-understanding-ruminal-acidosis-in-dairy-cows

- Firkins, Jeffrey L. “Feeding Byproducts High in Concentration of Fiber to Ruminants.” eXtension, June 29, 2010. Retreived April 12, 2019, from https://articles.extension.org/pages/26303/feeding-byproducts-high-in-concentration-of-fiber-to-ruminants

- USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. “Dairy 2014: Dairy Cattle Management Practices in the United States, 2014. Report 1.” USDA, February 2016. Retrieved April 17, 2019, from https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/nahms/dairy/downloads/dairy14/Dairy14_dr_PartI.pdf

- Todd, Richard et al. “Effect of feeding distiller’s grains on dietary crude protein and ammonia emissions from beef cattle feedyards.” USDA Agricultural Research Service, Proceedings of the Texas Animal Manure Management Issues Conference, September 29-30, 2009: 37-44. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://www.ars.usda.gov/research/publications/publication/?seqNo115=245905

- National Research Council Committee on Drug Use in Food Animals. The Use of Drugs in Food Animals: Benefits and Risks. “Chapter 8: Approaches to Minimizing Antibiotic Use in Food-Animal Production.” Washington, DC: National Academies Press. 1999. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK232568/

- National Research Council Committee on Drug Use in Food Animals. The Use of Drugs in Food Animals: Benefits and Risks. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. 1999. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK232568/

- CABI. “Animal Science Database: NSAD Approved for Lactating Dairy Cattle.” CABI, October 20, 2004. Retrieved April 17, 2019, from https://www.cabi.org/animalscience/news/13453

- USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. “Dairy 2014: Dairy Cattle Management Practices in the United States, 2014. Report 3.” USDA, February 2016. Retrieved April 17, 2019, from https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/nahms/dairy/downloads/dairy14/Dairy14_dr_PartI.pdf

- Charles, Dan. “FDA Tests Turn Up Dairy Farmers Breaking The Law On Antibiotics.” NPR’s The Salt, March 8, 2015. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2015/03/08/391248045/fda-tests-turn-up-dairy-farmers-breaking-the-law-on-antibiotics

- “Current H5N1 Bird Flu Situation in Dairy Cows.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 3 April 2025, www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/situation-summary/mammals.html.

- Hill, Meredith Lee, et al. “‘They Need to Back off’: Farm States Push Back on Biden’s Bird Flu Response – Politico.” Politico, Politico, 6 May 2024, www.politico.com/news/2024/05/06/bird-flu-dairy-farms-cdc-00156119.

- Moniuszko, Sara, and Céline Grounder. “Why the Latest Bird Flu Case Has Experts Worried about a Potential Pandemic.” CBS News, CBS Interactive, 21 Nov. 2024, www.cbsnews.com/news/bird-flu-pandemic-potential/.

- Schnirring, Lisa. “California Reveals Suspected Avian Flu Case in Child with Mild Symptoms.” CIDRAP, University of Minnesota Center for Infectious Disease Research & Policy, 19 Nov. 2024, www.cidrap.umn.edu/avian-influenza-bird-flu/california-reveals-suspected-avian-flu-case-child-mild-symptoms.

- Forster, Victoria. “FDA Study Finds Infectious H5N1 Bird Flu Virus in 14% of Raw Milk Samples.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 4 July 2024, www.forbes.com/sites/victoriaforster/2024/07/02/fda-finds-infectious-h5n1-bird-flu-virus-in-14-of-raw-milk-samples/.

- An, Henry. “The Adoption and Disadoption of Recombinant Bovine Somatotropin in the U.S. Dairy Industry.” Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, presentation at the American Agricultural Economics Association Annual Meeting, 2008. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/6278/2/465503.pdf

- Food & Water Watch. “rBGH: What the Research Shows.” FWW, August 2007. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://www.foodandwaterwatch.org/sites/default/files/rbgh_what_research_shows_fs_aug_2007.pdf

- Doohoo, JR et al. “A meta-analysis review of the effects of recombinant bovine somatotropin. 2. Effects on animal health, reproductive performance, and culling.” Canadian Journal of Veterinary Research 67, Issue 4 (October 2003): 252–264. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC280709/

- An, Henry. “The Adoption and Disadoption of Recombinant Bovine Somatotropin in the U.S. Dairy Industry.” Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, presentation at the American Agricultural Economics Association Annual Meeting, 2008. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/6278/2/465503.pdf

- Perkowski, Mateusz. “Dairymen reject rBST largely on economic grounds.” Capital Press, December 10, 2013. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://www.capitalpress.com/dairymen-reject-rbst-largely-on-economic-grounds/article_335ce36b-ec75-5734-9aad-80f11cae1d43.html

- USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. “Highlights of Dairy 2007 Part I: Reference of Dairy Cattle Health and Management Practices in the United States, 2007.” USDA, October 2007. Retrieved March 3, 2017, from https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/nahms/dairy/downloads/dairy07/Dairy07_is_PartI_Highlights.pdf

- USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. “Dairy 2014: Dairy Cattle Management Practices in the United States, 2014. Report 3.” USDA, February 2016. Retrieved April 17, 2019, from https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/nahms/dairy/downloads/dairy14/Dairy14_dr_PartI.pdf

- California Air Resources Board. “Documentation of California’s Greenhouse Gas Inventory. 11th Edition.” California Air Resources Board, June 22, 2018. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://www.arb.ca.gov/cc/inventory/doc/docs3/3a2ai_manuremanagement_anaerobiclagoon_livestockpopulation_dairycows_ch4_2016.htm

- Hopkins, Francesca M. “Greenhouse Gas Emission for Manure Management at California Dairies: Linking Observations Across Scales for Improved Understanding of Emissions.” University of California, Dairy and Livestock Working Group Joint Subgroups Meeting, July 27, 2018. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://arb.ca.gov/cc/dairy/documents/07-26-18/dairy_fresno_27july2018.pdf

- GRAIN. “Emissions impossible: How big meat and dairy are heating up the planet.” GRAIN and Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy, June 28, 2018. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://www.grain.org/article/entries/5976-emissions-impossible-how-big-meat-and-dairy-are-heating-up-the-planet

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. “Ag 101: Dairy Production: Lifecycle production phases.” EPA, (date uncertain). Retrieved April 17, 2019, from https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-07/documents/ag_101_agriculture_us_epa_0.pdf

- U.S. Geological Survey. “Nitrogen and Water.” U.S. Department of the Interior, January 17, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://water.usgs.gov/edu/nitrogen.html

- Whites-Koditschek, Sarah and Dukehart, Coburn. “Most nitrate, coliform in Kewaunee County wells tied to animal waste.” Wisconsin Watch, February 27, 2019. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://www.wisconsinwatch.org/2019/02/most-nitrate-coliform-in-kewaunee-county-wells-tied-to-animal-waste/

- Grossman, Elizabeth. “As Dairy Farms Grow Bigger, New Concerns About Pollution.” YaleEnvironment360, May 27, 2014. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://e360.yale.edu/features/as_dairy_farms_grow_bigger_new_concerns_about_pollution

- Cagle, Susie. “Wrangling the Climate Impact of California Dairy.” Civil Eats, October 20, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://civileats.com/2016/10/20/wrangling-the-climate-impact-of-california-dairy-methane/

- USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. “Animal Manure Management: RCA Issue Brief #7.” USDA, December 1995. Retrieved April 17, 2019, from https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/national/technical/nra/?&cid=nrcs143_014211

- Varnac, Marry. “Big Demand Driving Up Prices for Farmland.” The Columbus Dispatch, February 10, 2010. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://www.dispatch.com/content/stories/business/2013/02/10/big-demand-driving-up-prices-for-farmland.html

- International Dairy Foods Association. “Definitions.” IDFA, (n.d.). Retrieved April 17, 2019, from https://www.idfa.org/news-views/media-kits/milk/definition

- Brugger, Mike. “Fact Sheet: Water Use on Ohio Dairy Farms.” Ohio State University Extension, 2007. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://www.puroxi.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Water_Use_Dairy-copy.pdf

- Small, Virginia. “Concerns about high-capacity wells and pollution prompt central Wisconsin residents into action.” Wisconsin Gazette, April 5, 2018. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://www.wisconsingazette.com/news/concerns-about-high-capacity-wells-and-pollution-prompt-central-wisconsin/article_ec9f37c0-38e5-11e8-a233-1b785cd53c11.html

- Moberg, Glen. “Report Shows High-Capacity Wells Affect Little Plover River.” Wisconsin Public Radio, April 7, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://www.wpr.org/report-shows-high-capacity-wells-affect-little-plover-river

- Gardiner, Beth. “How Growth In Dairy Is Affecting the Environment.” New York Times, May 1, 2015. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/04/business/energy-environment/how-growth-in-dairy-is-affecting-the-environment.html

- Food & Water Watch. “Air Pollution From Oregon’s Large Dairies: Fact Sheet.” FWW, March 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from https://www.foodandwaterwatch.org/sites/default/files/fs_1702_oregoncafo-web_2.pdf

- American Lung Association. “Most Polluted Cities.” American Lung Association, 2018. Retrieved April 17, 2019, from https://www.lung.org/our-initiatives/healthy-air/sota/city-rankings/most-polluted-cities.html