Waste not, want not with “Ferment,” a new cookbook by Kenji Morimoto

A recent audit of my fridge yielded some troubling findings: two heads of broccoli, half an onion, a coral branch of ginger and two lemons (one still plump, one so puckered it looked like it had sucked on itself). And that was just the crisper. On the bottom shelf sat an enormous head of cabbage, some tofu, a droopy bundle of cilantro, the remnants of two separate meals and a tub of my aunt’s famous rice pudding. As someone who tries not to waste food, a knot of anxiety formed. What was I going to do with this clown car of perishables? The first thought that popped into my head was: broccoli stir-fry with tofu! The second was: How did I forget about that cabbage, those lemons, and the cilantro and rice pudding? And I need to eat those leftovers, even if my kid grouses about a meal cobbled together from day-old spaghetti and red beans and rice. The alternative — potentially tossing the food — is far worse. Between 125 and 160 billion pounds of food go to waste in the U.S. each year, much of it still perfectly good to eat; households are responsible for a considerable portion of that waste, more than 76 billion pounds of food per year to be precise. Will Aunt Roz’s rice pudding contribute to that statistic? Not on my watch.

Studies show that the best way to mitigate the food waste problem is to circumvent it: Whenever possible, we should avoid wasting food in the first place. While a big part of the solution rests in large-scale, systemic changes that prevent food loss, like countering agricultural overproduction and streamlining sell-by and best-by dates, the truth is that 40 to 50 percent of food waste happens at the household level. So there’s a lot regular home cooks can and should do, including buying less, planning better and using food before it spoils. And we can make a significant impact by discarding less of what is actually edible: by cooking from nose to tail or, better yet, skipping the meat and going root to shoot.

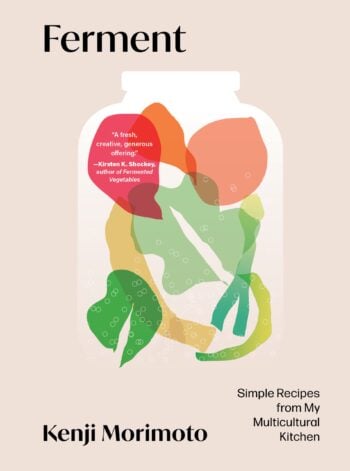

While managing food waste is not the primary goal of “Ferment,” a new book by fermentation aficionado Kenji Morimoto, it does offer two helpful pathways for tackling the problem at home. The first via an accessible education in fermentation itself, through the lens of six key techniques — from lactofermentation to cheong — each one chemically transforming bits and bobs of produce into something entirely, deliciously new. The second, via recipes that make use of these flavorful pickles and ferments, refashioning the surplus and scraps from one season into a meal, beverage or dessert in another.

When it comes to the ferments, Morimoto takes a flavor-first approach. He describes his culinary journey as a “constant search for flavor in the places I’ve called home” — a word that, for him, has described Chicago, Mumbai, New York, Hong Kong and London. That leads him to some surprising combinations of traditional techniques and nontraditional ingredients, such as a Beet Miso with Cumin & Allspice (the beet stands in for the traditional soybeans) and a Watermelon Rind Kimchi inspired by a daikon radish version called kkakdugi. Each of these recipes exemplifies Morimoto’s low-waste approach in different ways: The first makes use of the entire beet root, peels and all; the second elevates a scrap that is more often discarded than reinvented as something delicious in its own right.

As someone who loves fermented stuff but is more than a touch germaphobic, I’ve always struggled to balance my curiosity about trying the craft with my terror of food-borne illness. So I appreciate the approachability of Morimoto’s recipes, and his easy-does-it attitude throughout. His common sense “mantras” set a laidback, you-got-this tone early on, encouraging readers to “trust the process,” “trust your gut” and remember that “everything is fine below the brine” (a helpful mnemonic for anaerobic ferments that must remain submerged below the brine-line and out of the grips of that molecular party pooper, oxygen). Further, Morimoto notes that none of the recipes call for hot-water canning (phew!) and that “the environment for fermentation covered in this book is not hospitable to the bacteria that cause botulism” (phew again!).

Fears assuaged, the recipes suddenly look even more tempting, and continue to make good on the low-waste promise. The Garam Masala Sauerkraut offers to provide a loving, stable home for my neglected cabbage. The Zero-Waste Green Paste makes me think there just might be a longer life for the cilantro and ginger in my fridge — and actually, some of that ginger can team up with the lemon to make a spicy Ginger & Honey Kombucha. In the pickling chapter, Pickled Fruit, Three Ways, reassures me that an upcoming applepicking trip won’t result in unfulfilled pie dreams and yet more discarded food (I’m hoping to riff on the recipe for Pickled Pears with Thyme, Chile & Coriander).

And speaking of riffing, many of the recipes encourage it. A good number are stone soup-ish in their approach: Don’t have the herbs or fruit or veg called for? Use another! This same ethos applies throughout the second half of the book, where Morimoto presents dozens of recipes, from starters through cocktails, that employ the first section’s pickles and ferments. Morimoto introduces this section with a quick primer on how to cook with these salty-sour flavor bombs, noting, “I like to think of using ferments and pickles in cooking like ripples in water, with each circle expanding outward as we explore potential flavors and uses. … The power of ferments and pickles lies in how they can be combined, showcasing not only their tremendous diversity but also how their flavors evolve when they are used in cooking.”

Message received. I plan to try my hand at that masala-spiced sauerkraut. I’ll tuck it into a grilled cheese, as Morimoto suggests, and then use it in some fall bread baking when the weather cools. It’ll be the perfect foil for the next batch of Roz’s rice pudding.

Recipe: Garam Masala Sauerkraut

Kenji Morimoto, “Ferment“

This is my favorite variety of sauerkraut and was the first fun flavor profile I explored after I was confident with the basics. If you want to make this recipe even easier, swap the individual spices for a ready-made curry or garam masala blend; however, dry roasting the spices first and then freshly grinding them will release the natural oils and impart much more flavor, so it’s worth this additional step. This sauerkraut is incredible in a grilled cheese, the spices adding a lovely warmth to the melted cheese; mix it into a chicken salad or eat it alongside your next South Asian feast.

Prep time: 30-45 minutes | Fermentation time: 2-5 weeks

Makes one 1-liter (1-quart) jar

Ingredients:

800g (1.75lbs) white cabbage

1 small red onion about 100g/ 3.5oz, peeled and thinly sliced

2 mild red chiles about 30g (1oz), deseeded and thinly sliced

measured salt: 2% of the total weight of above ingredients

FOR THE SPICE MIX

1 tbsp coriander seeds

1 tbsp cumin seeds

2 tsp brown mustard seeds

1 tsp black peppercorns

1 tsp fennel seeds

2 green cardamom pods, crushed and seeds extracted

¼ tsp red pepper flakes

1 tsp ground turmeric

Method:

- Halve the cabbage. Shred it finely using a sharp knife or a mandoline. Place the shredded cabbage in a bowl with the red onion and chiles and calculate 2% of the total weight. This is the amount of salt you need.

- Add the salt to the vegetables and massage for 5–10 minutes, using a fair amount of pressure to optimize the creation of brine. If you do not see much brine, continue massaging the cabbage and a pool of brine should appear.

- Put all of the ingredients for the spice mix except the turmeric into a dry pan over a medium heat for 1–2 minutes until aromatic and the mustard seeds start to pop. Tip into a spice blender and blitz only a few times until it’s a coarse mixture; you can also do this using a mortar and pestle.

- Add the spice mixture and the turmeric to the vegetables and mix thoroughly.

- Decant into a jar and pack it down to ensure there are no air pockets, allowing the brine to gather on top of the vegetables. Use a food-safe fermentation weight to ensure everything is below the brine.

- Cover the jar and leave it at room temperature and out of direct sunlight for 2–5 weeks. After 2 weeks, start tasting. When you’re pleased with the flavor, move it to the fridge where it will keep indefinitely.

Recipe from “Ferment: Simple Recipes from My Multicultural Kitchen” by Kenji Morimoto © 2025. Reprinted by permission of the publisher, The Experiment. Available everywhere books are sold. theexperimentpublishing.com

Top photo © Dan Jones.

More Reading

How to host a sustainable dinner party

December 16, 2025

Tradwives, MAHA Moms and the impacts of "radical homemaking"

December 10, 2025

The FoodPrint guide to beans: Everything you need to know to buy, cook, eat and enjoy them

November 18, 2025

Your guide to buying and preparing a heritage turkey or pastured turkey this Thanksgiving

November 18, 2025

How Miyoko Schinner upped the game for vegan dairy

November 7, 2025

30+ things to do with a can of beans

November 4, 2025

In a beefy moment, beans?

November 4, 2025

For these cocoa farmers, sustainability and the price of beans are linked

September 17, 2025

You haven’t had wasabi until you’ve had it fresh — and local

September 11, 2025