Modern food packaging provides a way to make food safe, reliable, shelf-stable and clean. Unfortunately, most food packaging is designed to be single use and is not recycled. 1 Instead, packaging is thrown away and often litters our waterways. Because so much food packaging (especially plastic) has ended up in waterways, the United Nations has declared the plastic pollution of oceans “a planetary crisis.” This is a problem not only for humanity, but for all aquatic life. There are other environmental impacts from food packaging as well, including to our air and soil.

While it may be hard to find unpackaged food, opportunities to choose packaging that is less harmful to animals, people and the environment do exist.

Food Packaging Materials and Uses

Almost all food that we buy, especially processed food, comes packaged. Whether it comes from a grocery store or market, a sit-down or fast-food restaurant, an online meal delivery service or perhaps even the farmers’ market, it is hard to find food that isn’t artificially encased.

Modern food packaging is made from a variety of manufactured and synthetic materials, including ceramics, glass, metal, paper, paperboard, cardboard, wax, wood and, more and more, plastics. Most food packaging is made of paper and paperboard, rigid plastic and glass. 2

While some newer plastics are made from corn and other plant matter, most are made from petroleum and include additives like polymers. In addition, many types of packaging contain coatings and most packaging comes labeled with text using printer’s inks; paperboards are often lined with plastic that is not visible. 3

Types of Food Packaging

The type of packaging used depends on several factors, such as where the food is purchased, the intended use of the packaging and the timeline for consuming the product. For example:

- Grocery store food is typically sold in glass, metal, plastic or paperboard containers, and often comes encased in multiple layers. Those containers are then placed into plastic or paper grocery bags.

- Takeout food is often wrapped in plastic or aluminum foil, then placed into paper, plastic or Styrofoam containers, and (often) is put into paper bags and finally into plastic grocery bags. These bags may contain plastic cutlery, napkins and straws, as well.

- Processed food often has multiple layers of packaging; for example, a food item might be placed in a tray, covered in paper or plastic wrap, placed into a paperboard box and then, often, covered again in plastic wrap.

- Many food items that were traditionally found in glass, metal or plastic bottles or cans are now found in multilayer plastic-coated pouches or cartons.

Current food production and consumption practices generate a lot of packaging, and new forms of packaging are constantly being developed. The packaging of food places the largest demand on the packaging industry, with approximately two thirds of all the material produced going to package food. 45

The Impacts of Packaging on the Environment

Unfortunately, most packaging is designed as single-use, and is typically thrown away rather than reused or recycled. 6 According to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), food and food packaging materials make up almost half of all municipal solid waste. 7

In 2014, out of the 258 million tons of municipal solid waste generated in the US, more than 63 percent was of packaging materials (for food and other purposes) and, overall, only 35 percent (89 million tons) was recycled or composted. 8

The Trouble with Food Packaging

The trouble with food packaging begins at its creation. Each form of packaging uses a lot of resources like energy, water, chemicals, petroleum, minerals, wood and fibers to produce. Its manufacture often generates air emissions including greenhouse gases, heavy metals and particulates, as well as wastewater and/or sludge containing toxic contaminants.

Glass Manufacturing

In glass manufacturing, feedstock material is melted by burning fossil fuels, such as natural gas, light and heavy fuel oils and liquefied petroleum gas. Air emissions that result from combustion of fuels include greenhouse gases, sulfur oxides and nitrogen oxides. Emissions that result from vaporization and recrystallization of feedstock material include fine particulates that can contain heavy metals such as arsenic and lead. 910

Aluminum Production

Aluminum production is the result of mined bauxite that is smelted into alumina. This energy-intensive process uses a lot of water and creates a toxic sludge that is caustic and may contain radioactive elements or heavy metals, making its management complicated. Emissions include greenhouse gases, sulfur dioxide, dust, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and wastewater. 111213

Paper/Paperboard Manufacturing

The paper and paperboard industry use wood that is milled into pulp using either mechanical or chemical processes. It also uses plant fibers like cotton, linen and hemp, as well as grasses like straw, wheat and kenaf (an African fiber plant). 14 The manufacturing process can create air and water emissions. 15 Mills use a lot of energy and water; in the past, this produced large volumes of toxic wastewater. Now much of the water is recycled and modern processes in some mills produce no liquid effluents. 16 Primary air emissions include carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, volatile organic compounds and particulates. 17

Plastics Production

In the US, the major source of feedstocks for plastics production is natural gas, derived either from natural gas processing or from crude oil refining. 18 There are seven types of plastics polymers that account for 70 percent of all plastics production, including: polypropylene, polystyrene, polyvinyl chloride, polyethylene terephthalate and polyethylene, all of which are derived from fossil fuels and are used in food packaging.

Plastics manufacturing is responsible for a significant amount of greenhouse gas emissions in the US — as much as one percent. 1920 Other air emissions from plastics production include nitrous oxides, hydrofluorocarbons, perfluorocarbons and sulfur hexafluoride. 212223

Water and Land Pollution from Food Packaging

After it is used, most packaging is discarded and is either buried in a landfill or becomes litter that is carried along by wind and water currents into the environment. Packaging sent to landfills, especially when made from plastics, does not degrade quickly or, in some cases, at all, and chemicals from the packaging materials, including inks and dyes from labeling, can leach into groundwater and soil. 24

There is so much accumulated plastic in terrestrial and water ecosystems (by some estimates, 8300 million metric tons of plastic has been produced since around 1950) that some scientists view plastic accumulation as a “key geologic indicator” of our current geological time period (the Anthropocene). 2526

Litter — especially of the plastic variety — often makes its way to the furthest reaches of the planet, where it threatens human, avian and marine life. In the oceans, the problem has become so acute that the United Nations chief of oceans has declared plastic pollution of our oceans a “planetary crisis.” 27

The severe impacts of plastic on the environment are not limited to ocean pollution, however. One study estimated that one third of all discarded plastic ends up in soil or in freshwater. 28 Some scientists believe that microplastic (plastics less than five millimeters) pollution in soils around the world is an even more severe problem than microplastic plastic pollution in our oceans — an estimated four to 23 times more severe, depending on the environment. 29 Microplastics in soil have a number of detrimental effects, including impacting the behavior of soil fauna like earthworms and carrying disease. 30

Once in the soil and waterways, degrading plastics absorb toxic chemicals like PCBs and pesticides like DDT. The contaminated pieces eventually make their way through the food chain and into humans through ingestion of seafood. 31 The breakdown of plastics in soil and water also releases toxic chemicals like phthalates and Bisphenol A (BPA). 32

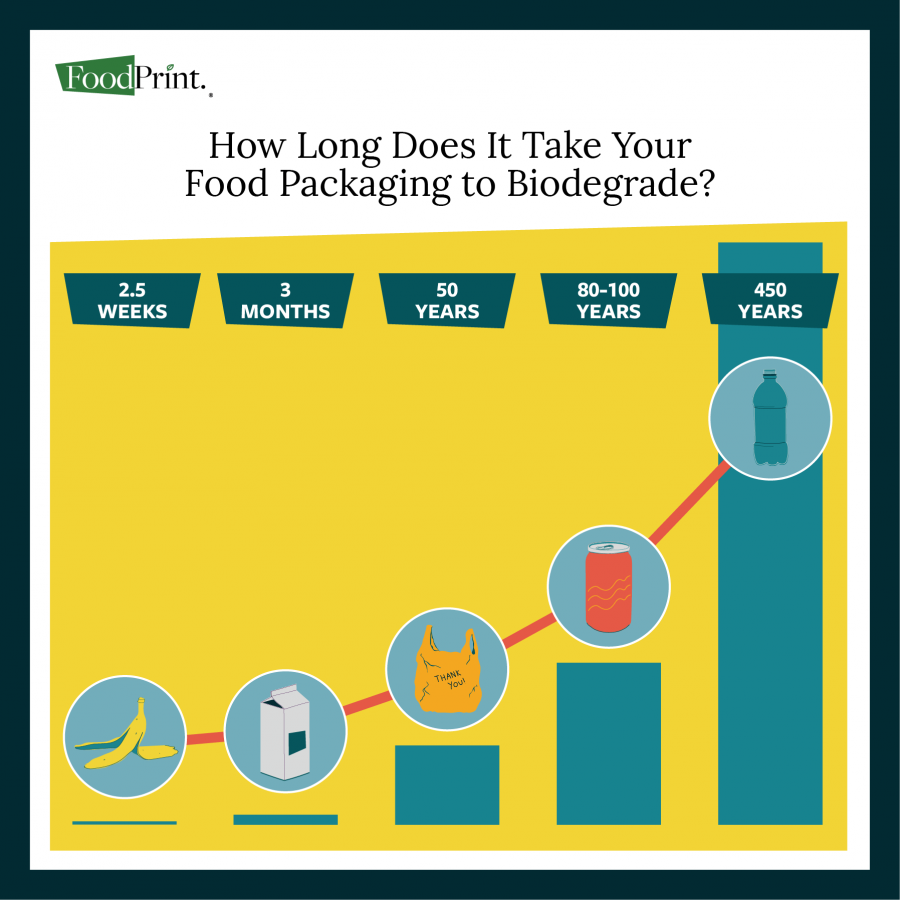

Some food packaging materials degrade relatively quickly; others will take hundreds to even a million years to degrade. The National Park Service has estimated degradation times of selected food packaging materials, as follows: 33

The Impact of Food Packaging on Birds and Marine Mammals

Beyond its unsightliness, as it spreads out to the far reaches of our planet, litter from food packaging poses a threat to marine life and birds; plastic is the worst offender, by far. Of all the coffee cups and lids, coffee pods, straws, Styrofoam containers, plastic bottles and their caps, plastic wraps, six-pack holders and plastic grocery bags, most is designed for single use. If it isn’t recycled, it often clogs our waterways, where animals mistake it for food or get tangled in it. 34

All the plastic floating around the oceans is incredibly harmful to animals. 35 Stories abound of dead birds found with stomachs full of plastics, turtles with straws stuck in their noses, whales with plastic bags in their stomachs and animals with plastic bags and six-pack rings wrapped around their bodies. According to Ocean Conservancy, “Plastic has been found in 59 percent of sea birds like albatross and pelicans, in 100 percent of sea turtle species and in more than 25 percent of fish sampled from seafood markets around the world.” 36

It is estimated that there are billions of pounds of plastic made up of trillions of pieces swirling around the oceans, carried along by the currents. Only about five percent of that plastic mass is visible on the surface; the rest is floating below or has settled out onto the ocean floor. 37 38

Air Pollution from Food Packaging

Food packaging waste that isn’t recycled or composted is typically landfilled or incinerated. While both options have benefits for waste management, they both produce air emissions, including greenhouse gases. 39 Landfills emit ammonia and hydrogen sulfide and incinerators can emit mercury, lead, hydrogen chloride, sulfur dioxides, nitrous oxides and particulates. 4041

What You Can Do

The way to reduce the impact from consumer packaging is to make better choices when we buy and consume food. As consumers, our food choices impact how much packaging we use and, therefore, how much trash and recycling we create. While recycling helps minimize the amount of packaging that makes its way to a landfill, some basic choices can eliminate the need for the packaging in the first place.

- Read our Report: Dive deeper on the environmental AND health impacts of food packaging.

- Take the Pledge! Eliminate single-use food and beverage packaging with our help.

- Eliminate the Need for Packaging.

- Use our tip sheet for how to reduce packaging when you shop and when you’re at home.

- Carry reusable shopping bags. Avoid plastic bags as much as possible.

- Carry reusable, stainless steel coffee mugs and water bottles (and read more about the impact of disposable coffee cups here). Use stainless steel straws (or go strawless!) for beverages instead of plastic straws.

- Help enact bag bans where you live. Many cities and towns have put bag bans in place.

- Buy and Eat Fewer Packaged Foods.

- Avoid plastic packaging, wherever and whenever possible.

- Buy the largest container available — single-serving sizes take more packaging. Or, where possible, buy foods from the bulk bin section of the grocery store, using your own containers.

- Make your own food from scratch when you can: whole foods require less packaging.

- Consider growing and canning your own food.

- Consider eating out/ordering delivery and takeout food less. Takeout/delivery involves a lot of packaging. 42

Hide References

- Bodamer, David. “14 Charts from the EPA’s Latest MSW Estimates.” Waste460, November 16, 2016. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://www.waste360.com/waste-reduction/14-charts-epa-s-latest-msw-estimates

- Muncke, Jane. “Food Packaging Materials.” Food Packaging Forum Foundation, October 2012. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://www.foodpackagingforum.org/food-packaging-health/food-packaging-materials

- Ibid.

- Shin, Joongmin and Selke, Susam EM. Food Processing: Principles and Applications, Second Edition, Second Edition. Chapter 11: Food Packaging. April 2014. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9781118846315.ch11

- Marsh, Kenneth and Bugusu, Betty. “Food Packaging and Its Environmental Impact.” IFT, April 1, 2007. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://www.ift.org/Knowledge-Center/Read-IFT-Publications/Science-Reports/Scientific-Status-Summaries/Editorial/Food-Packaging-and-Its-Environmental-Impact.aspx

- Bodamer, David. “14 Charts from the EPA’s Latest MSW Estimates.” Waste460, November 16, 2016. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://www.waste360.com/waste-reduction/14-charts-epa-s-latest-msw-estimates

- US Environmental Protection Agency. “Reducing Wasted Food & Packaging: A Guide for Food Services and Restaurants.” EPA, 2014. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-08/documents/reducing_wasted_food_pkg_tool.pdf

- US Environmental Protection Agency. “Advancing Sustainable Materials Management: Facts and Figures.” EPA, November 2017. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://www.epa.gov/facts-and-figures-about-materials-waste-and-recycling/advancing-sustainable-materials-management-0

- Ibid.

- World Bank Group. “Pollution Prevention and Abatement Handbook 1998: Glass Manufacturing.” World Bank Group, July 1998. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/1d345b80488551f8aa1cfa6a6515bb18/glass_PPAH.pdf?MOD=AJPERES

- US Environmental Protection Agency. “Final Air Toxics Standards for Clay Ceramics Manufacturing, Glass Manufacturing, And Secondary Nonferrous Metals Processing Area Sources: Fact Sheet.” EPA, December 2007. Retreived March 7, 2019, from https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-04/documents/2007_factsheet_areasources_clayceramics_glassmanufacturing_secondarynonferrous_metals.pdf

- Poppenheimer, Linda. “Aluminum Beverage Cans – Environmental Impact.” Green Groundswell, July 7, 2014. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://greengroundswell.com/aluminum-beverage-cans-environmental-impact/2014/07/17/

- Hydro. “Aluminum, Environment and Society.” Hydro, December 2012. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://www.hydro.com/globalassets/1-english/about-aluminium/files/aluminium_environment-and-society.pdf

- National Academics of Sciences Engineering Medicine. “Industrial Environmental Performance Metrics; Challenges and Opportunities.” Chapter 7: The Pulp and Paper Industry. The National Academies Press, 1999. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://www.nap.edu/read/9458/chapter/9

- US Environmental Protection Agency. “Pulp and Paper Production (MACT I & II): National Emissions Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants (NESHAP) for Source Categories.” EPA, January 2017. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://www.epa.gov/stationary-sources-air-pollution/pulp-and-paper-production-mact-i-iii-national-emissions-standards

- National Academics of Sciences Engineering Medicine. “Industrial Environmental Performance Metrics; Challenges and Opportunities.” Chapter 7: The Pulp and Paper Industry. The National Academies Press, 1999. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://www.nap.edu/read/9458/chapter/9

- Ibid.

- US Energy Information Administration. “Frequently Asked Questions: How much oil is used to make plastic?” EIA, May 24, 2018. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq.php?id=34&t=6

- Posen, Daniel et al. “Greenhouse gas mitigation for U.S. plastics production: energy first, feedstocks later.” Environmental Research Letters, 12 (March 2017). Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/aa60a7

- Plastic Packaging Facts. “Resins and Types of Packaging.” America’s Plastics Makers, 2018. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://www.plasticpackagingfacts.org/plastic-packaging/resins-types-of-packaging/

- Natural Resources Canada. “3. Greenhouse Gas Emissions from the Plastics Processing Industry.” Government of Canada, February 2018. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://www.nrcan.gc.ca/energy/efficiency/industry/technical-info/benchmarking/plastics/5211

- Pacific Institute. “Integrity of Science: Bottled Water and Energy Factsheet: Getting to 17 Million Barrels.” Pacific Institute, December 2007. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://pacinst.org/publication/bottled-water-fact-sheet/

- Thompson, Richard C. et al. “Plastics, the environment and human health: current consensus and future trends.” The Royal Society Publishing, July 27, 2009. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2009.0053

- US Environmental Protection Agency. “Getting Up to Speed: Ground Water Contamination.” EPA, August 2015. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-08/documents/mgwc-gwc1.pdf

- Geyer, Roland et al. “Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made.” Science Advances, 3(7) (July 19, 2017). Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://advances.sciencemag.org/content/3/7/e1700782.full

- Zalasiewicz, Jan et al. “The geological cycle of plastics and their use as a stratigraphic indicator of the Anthropocene.” Anthropocene, Volume 13, 4-18 (March 2016). Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2213305416300029

- Harrabin, Roger. “Ocean plastic a ‘planetary crisis’ – UN.” BBC, December 6, 2017. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-42225915

- Machado, Anderson Abel de Souza. “Microplastics as an emerging threat to terrestrial ecosystems.” Global Change Biology, December 15, 2017. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14020

- Ibid.

- United Nations Environment Programme. “Plastic planet: How tiny plastic particles are polluting our soil.” UN Environment, April 3, 2018. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://www.unenvironment.org/news-and-stories/story/plastic-planet-how-tiny-plastic-particles-are-polluting-our-soil

- Center for Biological Diversity. “Oceans Plastic Pollution: A Global Tragedy for Our Oceans and Sea Life.” Center for Biological Diversity, n.d. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/campaigns/ocean_plastics/

- United Nations Environment Programme. “Plastic planet: How tiny plastic particles are polluting our soil.” UN Environment, April 3, 2018. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://www.unenvironment.org/news-and-stories/story/plastic-planet-how-tiny-plastic-particles-are-polluting-our-soil

- National Park Service. “Lesson Plan: Things Stick Around.” US Department of the Interior, June 2016. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://www.nps.gov/teachers/classrooms/things_stick_around.htm

- Center for Biological Diversity. “Oceans Plastic Pollution: A Global Tragedy for Our Oceans and Sea Life.” Center for Biological Diversity, n.d. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/campaigns/ocean_plastics/

- Ibid.

- Ocean Conservancy. “Fighting for Trash Free Seas: Ending the Flow of Trash at the Source.” Ocean Conservancy, 2018. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://oceanconservancy.org/trash-free-seas/

- Winn, Patrick. “5 countries dump more plastic into the oceans than the rest of the world combined.” Public Radio International, January 13, 2016. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://www.pri.org/stories/2016-01-13/5-countries-dump-more-plastic-oceans-rest-world-combined

- Thompson, Richard C. et al. “Plastics, the environment and human health: current consensus and future trends.” The Royal Society Publishing, July 27, 2009. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2009.0053

- Marsh, Kenneth and Bugusu, Betty. “Food Packaging and Its Environmental Impact.” IFT, April 1, 2007. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://www.ift.org/Knowledge-Center/Read-IFT-Publications/Science-Reports/Scientific-Status-Summaries/Editorial/Food-Packaging-and-Its-Environmental-Impact.aspx

- Department of Health. “Important Things to Know About Landfill Gas.” New York State, n.d. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://www.health.ny.gov/environmental/outdoors/air/landfill_gas.htm

- US Environmental Protection Agency. “Wastes-Non-Hazardous Waste-Municipal Solid Waste.” Air Emissions from MSW Combustion Facilities. EPA, March 2016. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://archive.epa.gov/epawaste/nonhaz/municipal/web/html/airem.html#1

- University of California Carbon Neutrality Initiative. “Climate Lab. Episode Nine: Takeout creates a lot of trash. It doesn’t have to.” University of California, n.d. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from https://www.universityofcalifornia.edu/climate-lab