Plant-Based Cookbooks Are Finally Reflecting the World

Lyana Blount didn’t struggle to adapt the many classic Puerto Rican dishes she grew up with in the Bronx for “Black Rican Vegan,” the forthcoming cookbook named for her celebrated delivery company and pop-up kitchen. Comida criolla, as traditional Puerto Rican cuisine is called, isn’t big on dairy to begin with; what’s most important to figure out a replacement for is the pork and ground beef found in items like arroz con gandules (rice with pigeon peas) or stuffed into fried alcapurria and pastelillos. Those are easy enough to replace these days, Blount found, with items like coconut oil (a stand-in for lard) and her “must-have picadillo,” a plant-based version of the spiced ground beef mix, made with walnuts, shiitake mushrooms and a touch of liquid smoke that combine to create the umami, bite and richness that is expected.

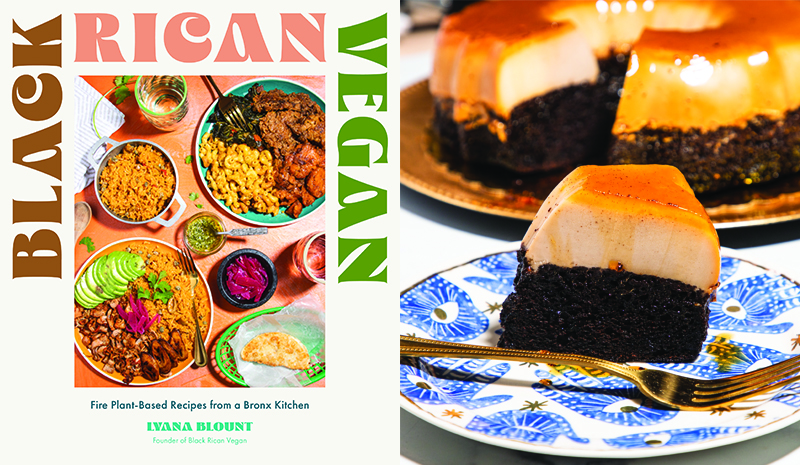

One dish, though, was a struggle: “It wasn’t too difficult for me to veganize Puerto Rican favorites,” Blount told me over email. “The most difficult was probably veganizing my flancocho.”

It’s not surprising to hear that this was a challenge. Flancocho, a newer classic, brings together a traditional custard-based flan and chocolate cake. Even the non-vegan version is difficult, requiring the baker to pour chocolate cake batter over an already-set custard, then bake it all in a water bath to ensure the caramel atop the flan doesn’t burn. After that, the flancocho rests overnight before the moment of truth when it’s flipped out of the Bundt pan. Blount’s version sets the coconut milk custard with agar powder, which can be grainy and make it tricky to nail the texture; she worked for three months to perfect it.

Writing a recipe that works is the challenge of every recipe developer, but there’s an extra level of pressure when removing animal products from cuisines that are regarded with pride and deep cultural significance. Any failure of flavor or execution will be blamed on the lack of eggs, dairy or meat, and it might even put someone off moving toward a plant-based diet.

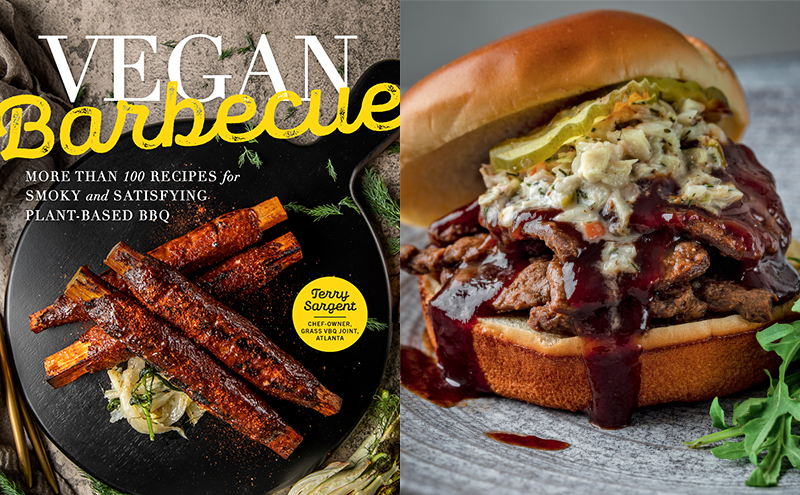

Despite these high stakes, there are more cookbooks like Blount’s coming out of late: “Plentiful” by Denai Moore; “Vegan Barbecue” by Terry Sargent; and many others that show how traditional cultural foods can be accessible and delicious while based in vegetables, legumes, grains and nuts. These are the latest in a wave established by “The Vegan Korean: Reflections and Recipes from Omma’s Kitchen” by Joanne Lee Molinaro and “The Vegan Chinese Kitchen: Recipes and Modern Stories from a Thousand-Year-Old Tradition” by Hannah Che, back-to-back winners (in 2022 and 2023) of the James Beard Media Award for Vegetable-Focused Cooking. Other recent titles include “Vegan Africa: Plant-Based Recipes from Ethiopia to Senegal” by Marie Kacouchia and Sally Butcher’s “Veganistan: A Vegan Tour of the Middle East & Beyond.”

Suddenly, it seems, the publishing industry has realized that vegan cooking is as rich and diverse as any other approach to the kitchen. Luckily, there are many chefs who’ve been working for years and are ready to bring their approaches to an emerging canon of plant-based cookbooks, a genre that has been historically white and focused less on complex flavor than convincing eaters that they’ll survive a meatless meal. This hasn’t necessarily been the fault of authors, but rather a lack of imagination on the part of the book business — entrenched, like many U.S. industries, in a culture that provides access to 224.6 pounds annually of red meat and poultry on a per capita basis, according to the USDA, despite livestock farming being responsible for 14.5 percent of human-caused greenhouse gas emissions. Meat is widely available, made cheap by government subsidies and beloved — why bet money on vegan titles, especially when the picture painted in the mainstream has depicted veganism as bland hippie food for white people, rather than a philosophy rich with culinary possibilities that can be mapped onto one’s own food traditions?

Google data has shown a drop-off in searches for the word “vegan” since an all-time high in January 2020, but interest in “plant-based” remains significant. With a new swath of cookbooks that apply this approach to the cuisines of diverse regions and ethnicities, perhaps a plant-based diet can seem like a world-opening rather than limiting path.

One of the most contentious culinary traditions to make vegan would, of course, be barbecue. But Georgia-born and -raised Terry Sargent first came to plant-based barbecue as an omnivorous chef, armed with deep kitchen experience and know-how. “To be honest, I don’t think I would have such success without my carnivorous background,” he says. “It gave me the blueprint to navigate the flavors needed to create Southern-style barbecue.”

Sargent gave up meat nearly a decade ago for health reasons, and began using downtime at what he calls a “boring” corporate kitchen position to craft recipes for mock meats. Ready-made freezer items from companies like Impossible Foods and Beyond Meat weren’t yet available, so he used his knowledge of seasonings and marinades to make jackfruit, tempeh and vital wheat gluten into meaty alternatives. This experimentation has paid off, says Sargent, who turned it into a brick-and-mortar business in 2020 with the plant-based Grass VBQ Joint, now located in Decatur. “I think it makes it more of a draw that we make all of our mock meats and recipes in-house,” he told me. “Creating your product in-house has a lot of benefits from food cost-saving to quality control. I can also cross-utilize a recipe and make it into three other recipes with our mock meat base, so it has its perks.”

“Vegan Barbecue” begins with a long chapter of salts and sauces, including a Scotch bonnet-based jerk marinade and a “sneaky cocoa faux meat rub” that uses cocoa to amp up the more standard flavors of smoked paprika and chili — essential to creating the satisfying, savory flavor for which barbecue is known. As Sargent told Southern Living when the magazine named him its 2021 Cook of the Year, “Barbecue is a way of cooking, not a type of meat.” It’s a common thread throughout plant-based cookbooks right now: illuminating the techniques and spices that create a cuisine and applying them to a wide range of plant-based ingredients both ready-made (tempeh) and more time-consuming (vital wheat gluten-based chicken). The approach encourages eaters to focus on flavors and textures rather than the lack of meat.

Denai Moore, in “Plentiful,” has tapped into something similar — as well as the reality that Jamaica, while having a meaty international reputation, is home to a robust vegetable-forward cuisine. “I feel like the most common misconceptions about Jamaican food is that it’s all meat and fried,” Moore told me over Zoom, “because Jamaica is an island that is laden with amazing produce, vegetables and dishes that were veg forward. I didn’t eat meat every day [in my childhood there], and so I have this great appreciation of all vegetables, fruits that were growing around me as a kid. So I guess this book was me touching base with that and utilizing the flavors — really imparting them on vegetables I love.”

The British-Jamaican musician turned chef also brings a global flair that one would expect from a longtime London resident. “[I] moved here when I was nine,” says Moore, “and so my story is quite unique, really. I grew up here with an entirely different accessibility to so many different cultures that I didn’t have in Jamaica.” In her book, jerk carrots are topped with salty vegan feta; callaloo, a Caribbean green, becomes a pesto for pasta; and hearts of palm mimic saltfish, with the addition of nori for that mineral taste of sea. These are Jamaican and broadly Caribbean favorites through Moore’s singular lens.

Blount, Sargent and Moore are writing a new script for vegan cooking, one that allows a person to show up to the stove as their whole self even when animal products aren’t in the ingredient list. The ease they bring to their recipes, too, shows that these dishes are born of real history, appreciation, love and understanding. These are the true facets of good cooking, not eggs, meat and dairy. The flancocho is still flancocho — still creamy, chocolaty and wildly rich — even when it’s set with agar.

Recipe: My Famous Flancocho

Lyana Blount, “Black Rican Vegan”

Serves 12

Flancocho is a custard that is baked on top of a chocolate cake. Flan is a popular dessert in Puerto Rico, normally made with condensed milk and sugar to make a custard. This flancocho was a recipe I worked on for three months to perfect, and it is now a popular item on the Black Rican Vegan menu. This dessert is sweet, and the custard texture mixed with the moist chocolate cake makes it a perfect bite every time. You’ll need a Bundt pan for this recipe, so make sure to plan ahead.

Ingredients

For the flan:

1 cup (200 grams) sugar

2 (13.5 ounces [400 milliliters]) cans organic unsweetened coconut milk

1 (8 oz [236 milliliters]) can sweetened condensed coconut milk

1 tablespoon (7 grams) agar agar powder

1 teaspoon ground cinnamon

1 tablespoon (15 milliliters) pure vanilla extract

Pinch of salt

For the chocolate cake:

1½ cups (188 grams) all-purpose flour

⅓ cup (37 grams) unsweetened cocoa powder

¼ teaspoon salt

1 cup (200 grams) raw cane sugar

⅔ cup (160 milliliters) avocado oil

1 cup (240 milliliters) water

1 teaspoon pure vanilla extract

1 tablespoon (15 milliliters) fresh lemon juice

Method

Make the flan:

- Get your 10-inch (25-centimeter) Bundt pan ready and set it on a flat and even surface.

- To a medium-sized nonstick pot over medium heat, add the sugar and caramelize, stirring constantly with a spatula, until it is golden brown. Working fast is vital because this will get very hot very quickly, and you do not want it to burn. Once the sugar turns brown and runny, pour it into the Bundt pan and use the spatula to spread it evenly on the bottom. Let the sugar harden. You may hear it start to crack — this is normal.

- In another pot over medium heat, whisk together the unsweetened coconut milk, condensed coconut milk, agar agar, cinnamon, vanilla and salt. Bring the mixture to a gentle boil while whisking, then remove it from the heat and pour it into the Bundt pan. Let the flan rest for 20 minutes, then put it into the refrigerator to solidify a bit for about 2 hours.

Make the cake:

- Preheat your oven to 350 F (180 C). In a large bowl, whisk together the all-purpose flour, cocoa powder, salt, raw cane sugar, avocado oil, water, vanilla and lemon juice. Mix thoroughly. Evenly pour the chocolate cake batter into the Bundt pan over the flan.

- Add about 8 cups (1.9 liters) of water to a deep, wide baking dish that is large enough to hold your Bundt pan. This will be your water bath, which will prevent the sugar from burning during the baking process. Place the Bundt pan into the water bath. Bake for 1 hour, checking on it periodically. Insert a toothpick into the chocolate cake and make sure no wet batter coats the toothpick — if so, the cake may need more time. When the cake is done, let it rest in its pan at room temperature for 40 minutes, then refrigerate for 2 hours or overnight.

- Use a cutting board or big plate to flip the Bundt pan upside down. You may have to run a knife through the edges or tap out the cake. ¡Buen provecho!

Reprinted with permission from “Black Rican Vegan” by Lyana Blount. Page Street Publishing Co. 2023. Photo credit: Mariana Peláez.

Get the latest food news, from FoodPrint.

By subscribing to communications from FoodPrint, you are agreeing to receive emails from us. We promise not to email you too often or sell your information.

Top photo by Mariana Peláez.

More Reading

How to host a sustainable dinner party

December 16, 2025

Tradwives, MAHA Moms and the impacts of "radical homemaking"

December 10, 2025

The FoodPrint guide to beans: Everything you need to know to buy, cook, eat and enjoy them

November 18, 2025

Your guide to buying and preparing a heritage turkey or pastured turkey this Thanksgiving

November 18, 2025

How Miyoko Schinner upped the game for vegan dairy

November 7, 2025

30+ things to do with a can of beans

November 4, 2025

In a beefy moment, beans?

November 4, 2025

Waste not, want not with “Ferment,” a new cookbook by Kenji Morimoto

October 1, 2025

For these cocoa farmers, sustainability and the price of beans are linked

September 17, 2025

You haven’t had wasabi until you’ve had it fresh — and local

September 11, 2025